By Carlene Bauer

Elle, July 2008

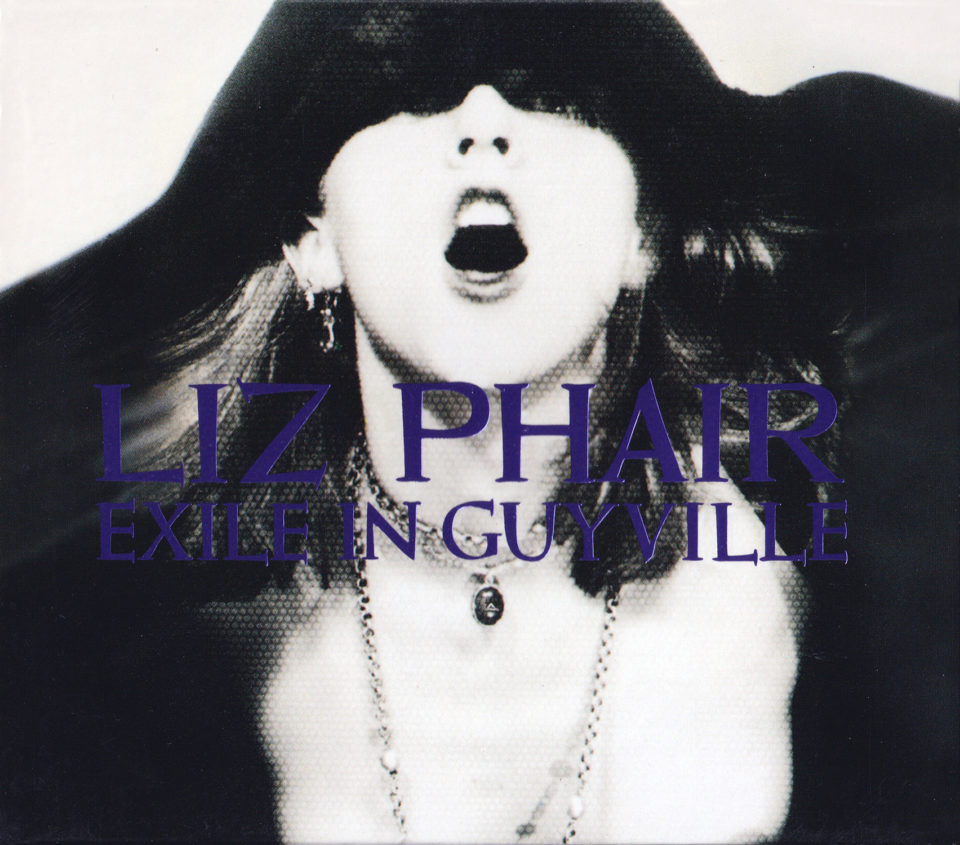

Fifteen years ago, Liz Phair released Exile in Guyville, a generation-defining record that spoke to daughters of the sexual revolution who wanted their freedom but also wondered if tenderness and romance had to be tossed out along with all the old rules. But guys loved the whip-smart songwriting too — Phair was a more laconic, less paranoid version of Elvis Costello. This summer, ATO Records will rerelease Guyville with four bonus tracks and a DVD documentary in which she interviews the males who inspired and worked on the record. ELLE spoke to Phair about what she’s learned since then.

ELLE: Why revisit the making of the record?

Liz Phair: Over the past few years, I’ve had a hard relationship with the press—people who had once been supportive of me were feeling betrayed, they felt that they owned Guyville. I thought, Wait a minute; I made that record. And I’d done some soul-searching, and I wanted to go back to the things that I’d put away—the creepy feelings I had in that time in my life. I had this stuff that I wasn’t dealing with. So going back and talking to every single guy of Guyville was not as hard as I thought and actually healing. I kind of recommend it.

ELLE: In your documentary you interview Ira Glass and John Cusack. What role did they play in the record?

LP: Brad Wood, my Guyville producer, said “You gotta interview Ira Glass.” Ira dated a friend of mine, so I knew him later, when I was married with a kid. So Brad said, “Don’t you remember that letter?” and I was like, “What letter?” and he said, “Ira Glass wrote this scathing letter, a review of your first show at the Metro [a venue in Chicago],” and it all came together and I was like, “That was Ira?!” I had him in my home later and we never talked about it! So that was the Ira connection. He remembered it too. He was like, “Why did I write that?” and I said to him, “I have to go back and look at my old press and I think ‘Why did I say that?'” Embarrassing megalomania. John Cusack, I was dating a friend of his. John had the New Crime Theatre Company in Chicago. Back then it was this scene of these Evanston [Illinois] kids doing crazy productions, and I would hang out with them. He was someone who inspired me back then. The stuff they were doing helped me when I was writing Guyville, because they took a lot of risks emotionally. They were completely out of control; they were saying things you weren’t supposed to say. And I would go back to my apartment and try to be a little more dangerous and outrageous with my own stuff.

ELLE: Were there any women in your life who inspired the same risks?

LP: I didn’t know women who were doing that until I started making music. I didn’t have exposure to that, except at Oberlin [Phair’s alma mater]. That really knocked my socks off — there was this inverted social system where the lesbians were on the top and the mainstream athletes were on bottom. So I came to Oberlin having a Lady Di haircut, wearing acid-wash jeans with flowers on them—like, “Hi! I’m Liz! And I wear really strong blue eyeliner!” And I got my ass kicked by all these New Yorkers. The zeitgeist on that campus changed my perspective completely on gender and bravery.

ELLE: When you were writing the record, circa 1991, when these guys saw you coming, what would they say?

LP: It depends on who you’re talking to. John would probably say, There’s that chick who’s dating my friend. I can think of getting kicked out of the [Chicago club] Rainbo for being a loudmouth, but I can also remember being shy. I was trying on a lot of different roles; I didn’t know who I was. I was trying to break out of the suburbs, and when I did break out, I don’t think I took my whole self with me — I think I played a role of being too cool and hip. At that stage, right before the record, I was trying to figure out who I was going to be as a person… do you remember that time in your twenties?

ELLE: That’s funny, because the record is a cohesive and assured statement.

LP: I realized when I was making [the documentary] that the record seemed cohesive and assured because I didn’t have my own identity. I was reactionary. That record was a very clear reaction to what I was exposed to over and over again. That was the best I could do for making a stand. I knew exactly what I didn’t want and that was really clear for me. It was definitely designed to take a crack at the male norm of rock ‘n’ roll. I was definitely swinging away at that piñata: Yeah, you guys get onstage and I’m tired of being the object of your song while you’re the subject. I wanted to take back the right to sexuality.

ELLE: Did you ever think that people were fixating too much on the songs about blow jobs?

LP: People thought it was this straight-up confessional diary of this naive person. I thought, “Don’t you get it’s kind of funny and I kind of know what I’m doing? But I’m not even sure that it comes through when I listen to Guyville now. When I listen now I think, That’s revealingly sad. I feel bad for myself because I can feel the pain. But at the time, I thought I was being quite clever, turning things on their head, sticking humor and wit in there.

ELLE: Sometimes I’ve thought that people have missed the fact that the music is pretty original, and that you’re using sound to ironically comment on femininity — for instance, you use a lot of piano, which is a standard suburban good-girl instrument, and set explicit lyrics to a melody that sounds like a madrigal. Is that intentional?

LP: You’re totally right…. I am not by any stretch a knee-jerk feminist, but I’ll call a spade a spade — I think that’s just plain old straight-up sexism. Guys don’t really don’t wanna hear if it’s really smart, and women feel uncomfortable if you reveal stuff they’re going to have to remember they did themselves.

ELLE: Has your son heard Guyville?

LP: No. With the record Liz Phair, a couple people said, “How dare she! What will happen to her son?” But if you came to my house you would see a guitar in my bedroom, and that would be the entire evidence of my job. There’s nothing wrong at all with women wanting to be women. Wearing a veneer of perfection never did me any good. If he knows that I have a sex life and he knows that I’m upset about things, it doesn’t mean I’m not a good mother, it just means I’m a human.

ELLE: Do you have any advice to give to the Liz Phair who made that record?

LP: I wish I could pour compassion and perspective into the person who made that record, because she was so clearly in pain. If I could just tell myself, “It’s gonna be okay, and you need to stop running away from the stuff that you’re scared of.”

ELLE: Is there any advice that she could give you now?

LP: [Laughs] Uh, yeah! It would be: Wake up! What Guyville teaches me right now, what I’m trying to take into new record, is that the biggest gift you can give the world is to share what truly happens to you, what really hurts, what’s really embarrassing. That’s the thing that Guyville had in spades that I got away from.

ELLE: Can you tell us about the CBS show you’re writing the soundtrack for?

LP: It’s brilliant. My friend from high school wrote it, and it’s about where we grew up [in the Chicago suburbs]. It’s called Swingtown, it’s set in the ’70s, and it explores the perfect suburban life through a couple that’s starting to swing. When I first got the script had to call my friend — my moral radar went off because I was breaking up with someone and felt that [drops voice low] love is an eternal flame and you have to guard it with your life. I was seeing how quickly things could go awry, and how you can’t go back from there, and I didn’t know if I could be involved in this show. But it’s beside the point that they’re swinging. It’s really about the writing and the relationships between the children and adults, and the adults who have money and who don’t, and the people who are exploring and the people who are threatened by it.

ELLE: What would Guyville Liz think of your last record, Somebody’s Miracle?

LP: She’d probably look at that and think, “How come you’re not living in a better house? Why aren’t you richer?” She’d probably be thinking, “We’re at this level?” Because of the polished sounds, because it sounds like it could be on the radio. Somebody’s Miracle was a funny record, because I liked a lot of the songs a lot, but the production wasn’t my favorite. So she would probably assume our life would be different if we were making music like that. This time around, I’m like, “Now listen. I want you guys all off your balance, I don’t want you to play pretty, we’re gonna do it now, and we’re gonna do it fast. We’re gonna do it my way.” And I’m all about doing it my way right now. Big time. It seems to be working so I’m gonna keep going.

ELLE: Do you feel there’s less of a need now in 2008 to make the record you made?

LP: No! There’s a serious dearth! You know what women took with their power? They went and put pictures of themselves giving blow jobs up on the Internet. Like, “Hi! I’m Mandy!” And she’s got a c–k in her mouth. Every sorority girl in the world has a shot like that and it oughta be on her MySpace page. And I’m like, “You didn’t get it! You didn’t get it at all!” I feel I had a tiny fractional hand in that, and I feel terrible because that’s totally the wrong outcome. I think a lot of young women have a lot more choices now and they don’t know where they came from. And we’ve got a long way to go, and every time someone bashes Hillary, I think, Do you not realize how sexist this is? Barack’s awesome, and so’s Hillary. You don’t have to date her. She doesn’t have to fit your prototype of what your girlfriend or mother looks like. She’s a politician…. The point was that we would have a good wide range of women putting out music of different types, and I feel there’s a lot of that happening, but there could be more.

ELLE: On that topic, a friend of mine wanted me to ask you: What the hell is wrong with the world, Liz?

LP: Ha! [Laughs.] Do you wanna know what’s wrong with the world? Progress goes too slow. There are too many machines being built and not enough thoughts being evolved. That’s what’s f–king wrong with the world. We keep building things and we don’t put the same effort into expanding our consciousness. Stop with the things! Just f–king stop! We have cars on Mars. Improve your relationships and stop putting cars on Mars. Start treating animals better. I don’t know. Figure out what real happiness is. There are just too many things being produced. [Pause.] I’m pissed.

ELLE: Endquote!

LP: That is a good place to stop!

ELLE: Are there songs on your upcoming record that Guyville-era Liz would approve of?

LP: Yes. I’m using that filter. I’ve gotta tell you, the ratio of ones I’ve written to the ones she would approve of are alarmingly few! She’s picky. I’m trying to live up to her, but she’s a real pain in the ass. But I feel nicely connected to where I began and haven’t felt that in a long time.