By Michael Brodeur

The Boston Phoenix, August 26, 2008

I’d love to get all swept up in the hullabaloo surrounding Liz Phair’s 1993, now seminal, now reissued (on Dave Matthews’s ATO Records) Exile in Guyville, I really would. I love hullabaloos. Thing is, I’ve always been more of a Whip-Smart guy. I think the songs are better, her band sound better, and her voice throughout doesn’t inspire bullshit lines like “Lilith Sternin at Lilith Fair.” Guyville, though? Really? I’m just not sure, guys.

I say “guys” because Phair’s career was, for better or worse, built on foundations of dude approval. (Girls loved her, but guys made her.) It’s Guyvilles simmering premise, after all — well, that and responding to the Rolling Stones, and passively confessing to a crush on Nash Kato of Urge Overkill. Years later, Phair has unshelved the songs that made her who she is (to everyone else, at least), directed a rough documentary revisiting the dude-heavy Chicago scene that chewed her out while eating her up, and set out to play Guyville in its entirety at select dates around the country (this Friday and Saturday at the Paradise).

Her career has been one of constant and drastic change (or selling out, as some would have it), from the raw pop of her early “Girly Sound” cassettes to her disconcertingly high-gloss output on Capitol. After paddling away from the “shores of cool”, as she sees them, Phair is allowing the tides to draw her raft back — but is that the same as washing up? I caught up with her on the phone as she was making her son breakfast.

Was there a point when you were fed up with Guyville — the attention and the expectations it brought upon you?

I’ve always had a rough time with it. I didn’t grow up wanting to be a rock star, I didn’t grow up wanting to be on stage. I got into music (in terms of writing it) at Oberlin, and half of that was because it was in fashion to do it. I wrote my crazy little songs, but I did it in my bedroom. It was a fun little fuck-off hobby.

But I got very serious when I made Guyville. I was on a mission to prove something. I was sick of these holier-than-thou music types that, for some reason, I was surrounded with. I just wanted to be like “fuck you, I can do it too — it’s not rocket science.” Then suddenly it became the defining thing of my adult life, at least until I had a child.

I came from a bunch of professionals — a lot of my family are doctors. Compared to doctoring — like saving lives or watching people slip away — everyone was so bejiggity about music. My dad worked with AIDS patients — I mean, that was heavy. I couldn’t go to him and say, “Dad! Whip-Smart is not as beloved as Guyville! What do I do?”

Aside from the know-it-all-ism that you’ve described, how did the dude overload that inspired Guyville affect your coming up in Chicago?

I actually became a better songwriter for it — they do know a lot of good music, and they exposed me to a lot of good music. I had my own go-tos challenged. Maybe in some ways in later years, my writing has suffered from the lack of that pomposity. My natural style coupled with the pressure cooker I was in to live up to these musical ideals that these guys had espoused was a winning combination. Could I immerse myself in that again? No way in hell.

Was there anything you liked about being in Guyville? Did a community of dudes provide anything that a bunch of girls couldn’t?

It’s less “what did I get out of it” and more “what did I suffer through”. Nobody let me talk! Even in the documentary, every single one of them is so fidgety and anxious to start talking again. They would politely wait and let me talk — Ira Glass wasn’t like that, and John [Henderson] wasn’t like that, but the music dudes were like, “Shut up and let me talk now.” I used to have to shut up and listen all time, and it was crazy frustrating — but I did learn a lot.

I read an infamous letter Steve Albini wrote to the Chicago Reader in 1994 to ream their music critic, Bill Wyman, and to point out that you were “A persona completely unrooted in substance, and a fucking chore to listen to.” Then I read the shitstorm that ensued in the letters section and was struck by how fiercely Chicagoans defended their scene.

It wasn’t so nice. But Steve Albini was one of my favorite interviews in the documentary. I had to acknowledge that, in a lot of ways, he’s been correct the entire time. It’s a tangled Web because all these people I had problems with, I was also a fan of. We were all in this complicated soup. The fact that people cared so dearly and passionately about their scene back then is admirable and rare. Now in our culture you are being fed “cool” all the time. Back then you had to find cool. Once reaching the shores of cool, you felt like a survivor.

In the wild, when Liz Phair comes up, there’s usually a distinction inserted about “Old” Liz Phair (Guyville) versus “New” Liz Phair, in part because of obvious changes in the production values, but also because the songs are way less oblique. Do you acknowledge distinctions like that?

Oh, I totally get it. I hear the difference. I hear the pop period. The thing that I do that no one else does is, I never start with Guyville — I go all the way back to Girly Sound, which was kind of silly and pop back then. I went serious on Guyville, I went rock on Whip–Smart, there was the pregnancy and storytelling on Whitechocolatespaceegg, then the pop manifestation on Liz Phair, and then the fucking compromise disaster of Somebody’s Miracle.

I see the totality. At different points, I bring forth one or the other approach based on whatever world I’m in. I think artists should be allowed to experiment. I would be bored to death if I just did the same thing over and over again. In my book, it’s different things, the same body. You can find Liz Phair in Girly Sound. If you can’t hear it, you’re really not listening.

But your songs have changed structurally, as well. For instance, I’m more of a Whip-Smart person, and one reason for that is the way you’d just repeat a line 30 times over. Was that something you were just trying out?

You’re a smartie, and that was, for that record, the defining feature. That was the gig I was playing on that record, I was trying out mantras. When you repeat something over and over again, does it become more clear, or does it lull you out? That’s what I was into. I wanted to know how many times you could say it, how the meaning would morph.

But that’s also gonna be the road not taken for me. You could talk to Kim Gordon or Aimee Mann and we could have this discussion: is it rich for you that you’ve sort of tracked the same territory over and over again? It really could have been what I chose to do, but I just went all over the place. And it probably could have been rich, and the meaning could have kept deepening or changing. It could have been my life, and probably a very happy one. I went the other way. I went flashy and dashy.

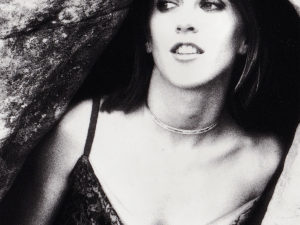

Featured Image: Liz Phair in 1993 (Photo: Robert Manella)