10. “Fuck and Run”

Twenty years later, what’s there to say about “Fuck and Run”—one of the most talked about songs of the ’90s, on one of the most discussed albums of all time—that hasn’t already been essayed, blurbed, blogged, or Tweeted?

It’s far and away the quintessential Liz Phair track, that pin in the early ’90s female singer-songwriter haystack that even the most casual listener can spot, with its infamous title and infinitely sing-along-able, blush-inducing chorus (“Fuck and run / Even when I was 17 / Fuck and run / Even when I was 12”). And after two decades, it is one of those rare musical occasions where diehard fans haven’t sickened of spinning their idol’s “hit” (even though “Fuck and Run” never played on mainstream radio), nor do they sour at the notion that at a current day, Phair shows a quarter of the crowd may have purchased a ticket just—well, mainly—to hear that one tune. (Ironically, I recall attending a show at Roseland Ballroom in New York City during the 2003 Liz Phair tour and witnessing the horror of teenage girls and their fathers watching Liz tear through “Fuck and Run” shortly after shuffling about her aw-shucks-with-a-“fuck”-tossed-in hit “Why Can’t I?”).

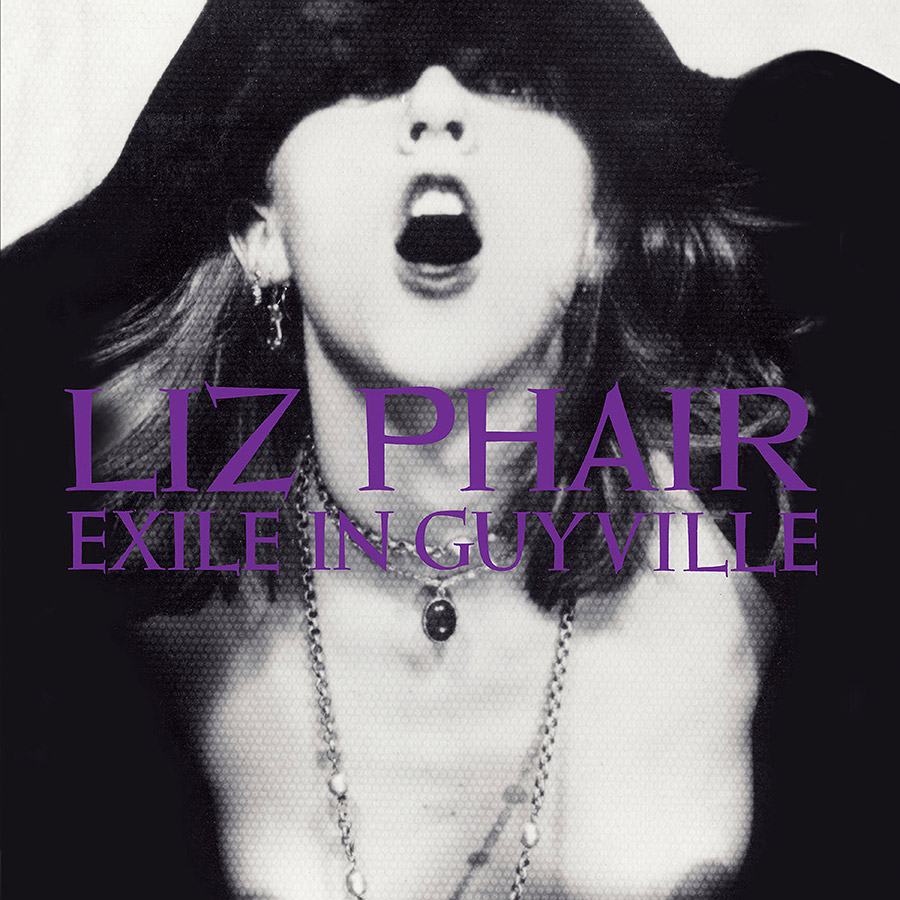

Simply put, “Fuck and Run” is a bona fide classic. As I posited in the introductory essay for this series, Phair, despite a few major musical missteps and public displays of not quite knowing what she’s doing with herself (which I suspect will retrospectively endear her and play an important role in the next chapter of her career’s narrative, and since she’s in her early 40s, looks about 25, and still thinks like a rascally, rebellious teenager, I’d say she has plenty of time and talent to reinsert herself into the current music conversation), has seemingly been given a lifelong pass because of the wonder that is Guyville — and “Fuck and Run” is largely to thank. Over time, it’s become a sort of a rite of passage song for a generation of women who attended (endured) college (boys) in the ’90 and early oughts, a piece of sonic text that both shaped their musical palettes and, for better or worse, sense of self. As I conceived of this Between the Grooves entry, I decided there would be no better way to celebrate and examine “Fuck and Run” than to chat with some of the very women who were introduced to the song and its creator during the very period Phair is singing about, navigating the rocky terrain of romantic relationships, self-respect, and everything in between.

This lively panel included five women, all friends, all freshly 30, all of whom connect to and understand Phair’s seminal one-night stand parable in light of their own ideas and experiences from the time they first heard “Fuck and Run” to the present: writer and college instructor Sarah Goffman; surgical resident Keelin Roche; lead singer of La Defense Hillary Kover; music writer and social worker Alena Kastin; and international art shipper Martha Hart, whose dog Hazel lay in the center of our wine-fueled discussion, groggy from having been spayed the night before, which seemed especially appropriate…

[We begin by watching a clip of Liz Phair, circa 1995, wracked with stage fright, belting “Fuck and Run”.]Keelin: This brings me instantly back to college. Right back to my dorm room freshman year.

Sarah: Yeah, it’s interesting because we all discovered the album almost a decade after she released it. So we discovered it in the time period that the album is about.

It’s interesting because, on the record, this comes right after “Mesmerizing”, which up to that point feels like most mature song on the album, a real reflective line in the sand, where Phair’s referencing the previous songs and expressing an exhaustion and intolerance with what’s transpired. But then “Fuck and Run” bursts open and with it is a sort of immaturity. She’s suddenly regressed to this bad behavior, waking up in a stranger’s bed. And that duality — or hypocrisy, depending how you see it — rings true for the album as a whole because it’s both juvenile and profound to just plainly say, “I want a boyfriend”.

Sarah: It’s also kind of tongue-in-cheek and kind of self-conscious. I definitely went through [the same thing] being a woman in your 20s and coming into your sexuality and trying to feel like you’re independent and tough, and so you get in this mindset where you’re like, “I can do that, I can fuck and run, it doesn’t bother me. I don’t need to be one of these girls that needs a boyfriend or any of that stupid shit”. But the truth is you do want it too. It’s not satisfying or fulfilling to just date around. So when you feel needy like that, you have to be ironic about it: “Oh look at me, I’m so stupid, I’m such a typical girl, I want a boyfriend, bla bla”. But you’re never sure if you feel unfulfilled or ashamed because people make you think you’re supposed to feel ashamed.

Martha: There’s also a kind of overreaction too. Liz is maybe asking for it because she deserves it and not because she wants it. And that’s why she’s waking up in this guy’s bed, because it’s her habit too, but she knows she deserves better, and women should be treated better than this. She’s like, “Man, I want all these old-fashioned things”, because that’s how a woman deserves to be treated, but not necessarily how modern women want to be treated.

Sarah: And it’s confusing when you’re brought up and taught in the age of Sex and the City; you don’t need to be tied down to one man. You can own your sexuality and do what you want as long as you’re safe or whatever, so it’s confusing about how to do that and still treat yourself right.

But even Sex and the City, which debuted just a few years after Guyville, ends with Carrie marrying the guy who treats her like shit for a decade…

Keelin: Yeah, she marries him! And then, in the movie, he screws her over again!

There’s a similar theme in Guyville. Liz both critiques and exonerates these men for the way they are, sees the men getting away with shit, and is mad at herself for her part in letting them. She understands and pities them but also owns up to her contributions to the problem.

Keelin: It’s funny because when I listened to Guyville, and this song in particular, I always felt totally connected to her, and I really understood what she was saying, but I’ve never done that. I’ve been a serial monogamist since I was 18, but yet I feel like I totally understand. I think it’s a woman thing.

Martha: When I connected to this song the most, I had a steady boyfriend. I had the things she was asking for, I guess. And yet I really connected to it, like, “Fuck yeah, I get that”.

Alena: Maybe the reason it is easy to relate to despite not being in the same position she describes in the song is because it addresses feelings of disconnection, different needs, or goals in a relationship. And that can feel familiar from even the most insignificant interactions when you’re trying to negotiate starting a relationship, or even over the course of a relationship’s ups and downs.

Hillary: When I listened to this song years ago, I felt totally unable to relate. I love you, Liz Phair, because you are cool and because you remind me of the women in movies that I think of as heroes in the ’90s — Doc Martens and eventful lives and friends in bands and Seattle — but I can only listen to this song on headphones and pretend that this is my story, this is definitely was not my reality. To me, it always felt like a soundtrack. Something to march down the street to, but when doing so, I think I probably felt ridiculous, playing a role.

And I wonder if Liz even really did that herself. Fucking and running. She may not mean that literally, of course.

Sarah: But in a very literal way, it really does express what it means to be single at that age, always kind of lying to the way you present yourself to guys so much that you convince yourself of it. Like, “I’m cool; however, you want to be in this, no attachments, man, whatever, I’ll wait. It’s fine”. You’re so afraid of admitting that you want a relationship that you convince yourself you don’t want it.

Martha: But isn’t Liz also a little cooler than us? Wasn’t she more of a player?

I think it might have also just been the time period. She was at Oberlin in the early ’90s, she was just coming of age in the rebirth of feminism, where young men were, in a way, revering strong intelligent women, certainly far more than they do now. It was a brief blip, I think. And maybe part of what made Liz’s music so striking was that she could see through it and could foresee its end.

Sarah: But she wouldn’t or couldn’t have written this album the way she did unless she was really affected by what she’s singing about. Maybe she slept around, or maybe she didn’t, but whatever it was definitely had an emotional tax on her.

Keelin: I don’t think the way she presents it in this song; it’s something she wants but engages in.

Sarah: Something she’s resigned to with a sort of comic reluctance.

Keelin: But that “even when I was 12” comment always brings me to my psych background, like hmmm, what’s she dealing with there?

Hillary: Well, there’s this thing about the song. I never know whether to take her seriously. There’s a shock element. “Even when I was 12” is kind of vulgar and gritty, but she comes off so self-conscious [when she sings it]. When I listen, I feel like I’m watching a movie. Reality Bites. Like I said, those female heroes from the ’90s. I feel like she’s singing for a generation, but I actually can’t tell how much of it is about her or how much of it is her playing a role. Do you know what I mean? Maybe that’s my own inability to relate, but I do have a hard time always believing her in this song.

Sarah: It’s also sort of a trope, even though it’s weird to call someone’s experience a trope, but there’s this female singer-songwriter of the ’90s sexual abuse or violation theme that was prevalent like with Fiona Apple and Tori Amos, so the mind goes to that. And in that song “Glory”, she says it is circa 1981, so she would have been like 14 the first time someone went down on her, so it does make you wonder if she was, in fact, sexual at that age.

It’s a shocking lyric for sure. But does it have to be literal? Is it middle school blues, or it is something more than that?

Keelin: Yeah, you’d sing along, and then sort of your voice goes down when you say, “Even when I was 12”…?

Martha: And that’s why I go from “Yeah, this is our story” and then you hit that part, and you’re like “Um no, that’s your story!”

[Everyone laughs.]Sarah: It’s an awkward line.

Hillary: It is an awkward line! Kind of an abrupt confession or maybe a cry for help. Is she serious? Very uncomfortable. But maybe it’s more about these repeated patterns she’s observed in herself throughout her life than literal, her tendency to give in to men, even as a young girl, she did this… submitted, resigned [to them]. Or maybe mentioning her 12-year-old self is a reminder that she was 12 at one time, that it’s not so distant, still part of her, still feels like a girl. And so many of the songs are so girly sounding, childlike. I think that’s really important. Songs written in the bedroom on the guitar. Songs that sound like lullabies. This song songs like a chant or an anthem. A schoolyard song. Written for girls and meant to be sung by a group. Girly songs, grown-up problems.

And musically, at the end, the drums trails off after the final time she says it, and leaves us stewing in that uncertainty, that awkwardness. Then the song after “Fuck and Run” is “Girls! Girls! Girls!” in which she talks about “taking full advantage of every man” she meets and how she “gets away almost every day with what the girls call murder”. She’s suddenly trying to convince us that she’s the user and the player?

Sarah: That’s the constant vacillation we hear on that song and on the whole album.

Martha: And maybe she doesn’t want to fuck and run, but would she even be a good girlfriend? Does she know how to be a loving partner? She says, “I want a boyfriend”, but never says, “I want to be a girlfriend”. She wants the guy to make a gesture, but she’s also living a lifestyle where she maybe doesn’t want it.

Sarah: I think we all vacillate between that. “I want to be independent, I want to invulnerable, I want a boyfriend, I don’t want to be alone.”

The line “I can feel it in my bones / I’m gonna spend my whole life alone” — what a terrible indictment. She makes it sound like a disease.

Alena: I think we all feel that way sometimes. Or, at the very least, those extreme beliefs about ourselves that, while they may not be true, can pop up at moments in our lives when we are vulnerable.

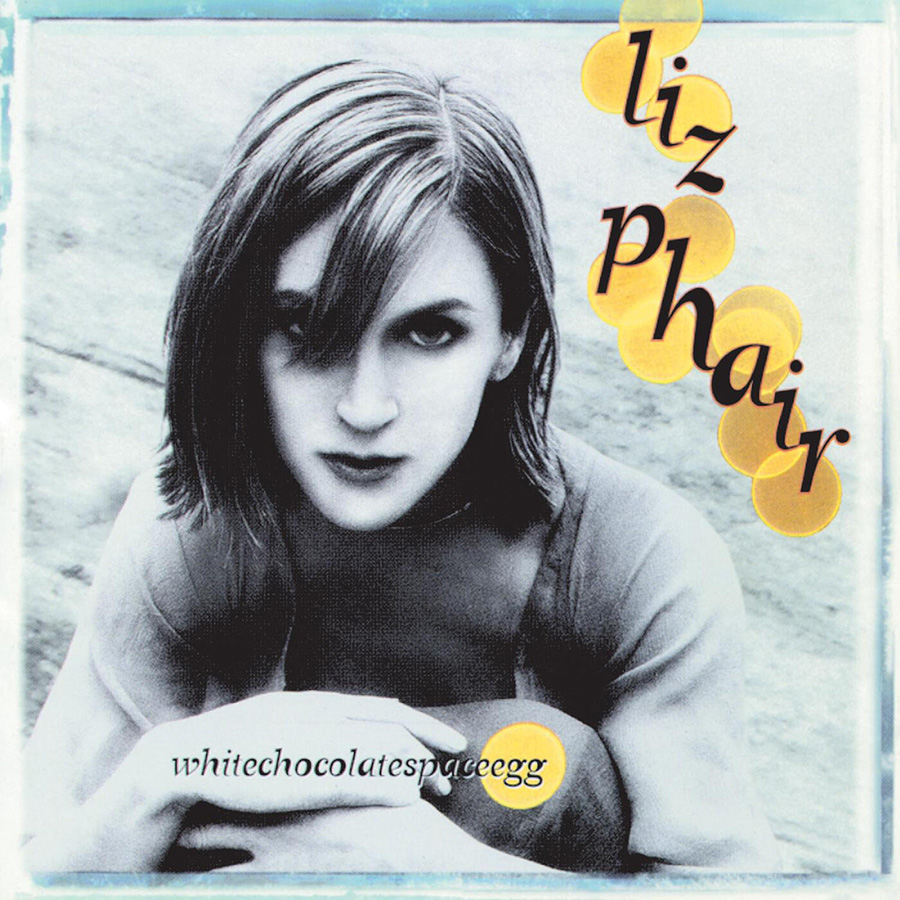

Sarah: But didn’t she get married shortly after Guyville?

Right, and had a son, and then pretty quickly divorced. And then, a few years later made her pop album. She didn’t want to make a sad divorce album, so she swung in an opposite, unexpected direction instead. She seems to have a history of kind of getting somewhere but pulling back like she’s enacting that fickleness on the albums in her life, or vice versa.

Martha: But god, she looks so hot these days, in her 40s. So amazing.

Sarah: Yeah, and it’s hard not to feel for her because you can release a few successful indie albums and still have no money.

Keelin: Shit, is this because I was listening to her on Napster in college?

[Everyone laughs.]Tell me something that you felt when you listened to “Fuck and Run” years ago that still rings true and something that feels 10, or maybe 20 years later, you can’t quite relate to anymore.

Alena: Well, my first exposure to the song was when I was in high school, and I remember feeling so rebellious singing along, although I honestly could not relate to most of what she is singing about. I definitely felt the angst of the song, and the feelings of longing and regret, though I guess for me it was more of a longing for that sense of maturity and experience, a time when I could really know what it feels like to have been burned by men, to have had relationships, even ones that went sour. Because at that time, being a teenager, my life felt sort of slow and boring, and the type of 20-something life where I might really end up in someone’s bed one morning like the lyrics describe felt very cool. Obviously I now see that what Phair is singing about is not exactly something to idealize. Though when I listen to the song now that I am older, I don’t find it to be a sad or depressing either. I still feel that it is empowering in a lot of ways — partially because it still feels a bit naughty and subversive to sing the words “fuck and run” over and over — and also because she is being so frank and honest about what she wants. I think being so honest may actually come more naturally when you are younger — think about all those books of poetry and song lyrics buried somewhere in a box in your teenage bedroom — but as we get older, we intellectualize things and communicate differently. So while the lyrics and sentiment in the song affect me differently now, I respond to them for their honesty and authenticity.

Sarah: For me, it’s always having that feeling that this is going to be the rest of my life because it didn’t work out with this guy. And an interesting mirroring of when something goes good that it is also going to be the rest of your life. I still relate to the yearning, that raw angst of the sentiment. What I no longer relate to is that I wouldn’t get myself in that mess in the first place. Waking up in that position, metaphorically or literally. I feel like I used to sing along to “Fuck and Run” with a little bit of pride, like, “This song is about me too”, but now I sing along to it with, “Yeah, I know what that’s like, and I’m never going to be in that position again!”

Martha: Originally, I’m not sure what it was that drew me to this song because I was in a happy relationship. Maybe because I wanted to be in that place, secretly? Or maybe because you don’t have to wake up in a one-night stand to feel like guys are idiots — you can just date them and feel that way! [laughs] So the lyric that gets me now is, though I hadn’t been as obsessed with that lyric before, is when she wonders about the “kind of guy who makes love ‘cuz he’s in it”. I was like, “What is she talking about exactly?” Letters and sodas, that sounds like a boyfriend, but it’s not guaranteed. It’s traditional, it’s protocol, right? When she says, “Whatever happened to a boyfriend”, it makes sense because these are the things a boyfriend does. But the lyric about a man making love because he’s in it, that sort of loses me now. It’s not because it’s not relevant to my life or experience, but that’s not the same thing as a one-night stand and a relationship. I get hung up on that more now than I used to. Affairs can be very passionate. The situation she’s describing doesn’t always have to be so terrible.

Sarah: And just because you have a boyfriend doesn’t mean that you’re going to feel that passion.

Keelin: So you’re saying that anybody can do that; you don’t need the boyfriend to feel that?

Martha: Exactly, that doesn’t define a “boyfriend”. And maybe Liz is talking about a fantasy. She’s singing like it’s a totally extinct thing.

Keelin: I think, like Martha, I don’t really know what exactly drew me into it so much. I never really personally felt what she felt, but the whole album was just… college for me. But I think part of what draws me to it now, which is maybe what back then did too, is that it is a fantasy life for me. Like, I didn’t have one-night stands, and I didn’t do that kind of thing, but maybe somewhere inside of me, I feel like I could do that. And I saw it happening around me. Getting married and everything, what was scary about it — and I love my husband, and being married is totally wonderful — but letting go of that fantasy of maybe having that type of relationship…

Sarah: Like, a problem that you sort of wish you had.

Hillary: Yes, I agree with you guys. A fantasy of a life that you’re not living. That was a huge problem for me when I was young. Still is. Actually, when I was younger, I was so focused on wanting problems! So distressed that I didn’t have more grit and depth to my own story. This is probably a big part of why I liked the album so much, not just the song per se, but the album. This older woman, with her man problems. So fascinating, exotic. Like maybe something to look forward to.

Martha: But also the fantasy of her as a rock ‘n’ roll star. Forget what her sexual relationships with guys are. She showed them off with music. She beat them. And that’s part of the fantasy too. You hear her struggling with men sexually. But what I fantasize more about having is being such a badass and being a songwriter.

Sarah: And being successful at something men are usually good at. That’s definitely a theme from the album.

The original version of “Fuck and Run” from the Girly Sound bootlegs — which she made because she was challenged and egged on by some male musicians — flips the tables a bit at the end. She sings, “You didn’t think this would happen again” and “You want a girlfriend / You want all that stupid old shit / Like letters and sodas”. And it ends that way. And when we consider the title, we’re never sure if she’s been exiled to or from Guyville because “in” is so purposely ambiguous.

Hillary: And I actually discovered the album through my college boyfriend and his guy friends. They were kind of music nerdy. But cocky! And the album stood out to them. They were so impressed by it, so into it. Exile in Guyville and Lucinda Williams’ Car Wheels on a Gravel Road both albums were being played a lot that summer. Funny to think that the two albums came into my life at the same time and that it was men that introduced the albums to me.

Keelin: It’s funny, that sentiment of her being exiled, like this idea of her being a man, being able to transcend into being a “guy” or able to be a man or whatever, that was part of what drew me to surgery. Surgery is historically this super male-dominated thing, and being a woman in surgery is fucking badass. And I was like, “Yeah, I want to do that. I want to be fucking badass.” That I can relate to.