11. “Girls! Girls! Girls!”

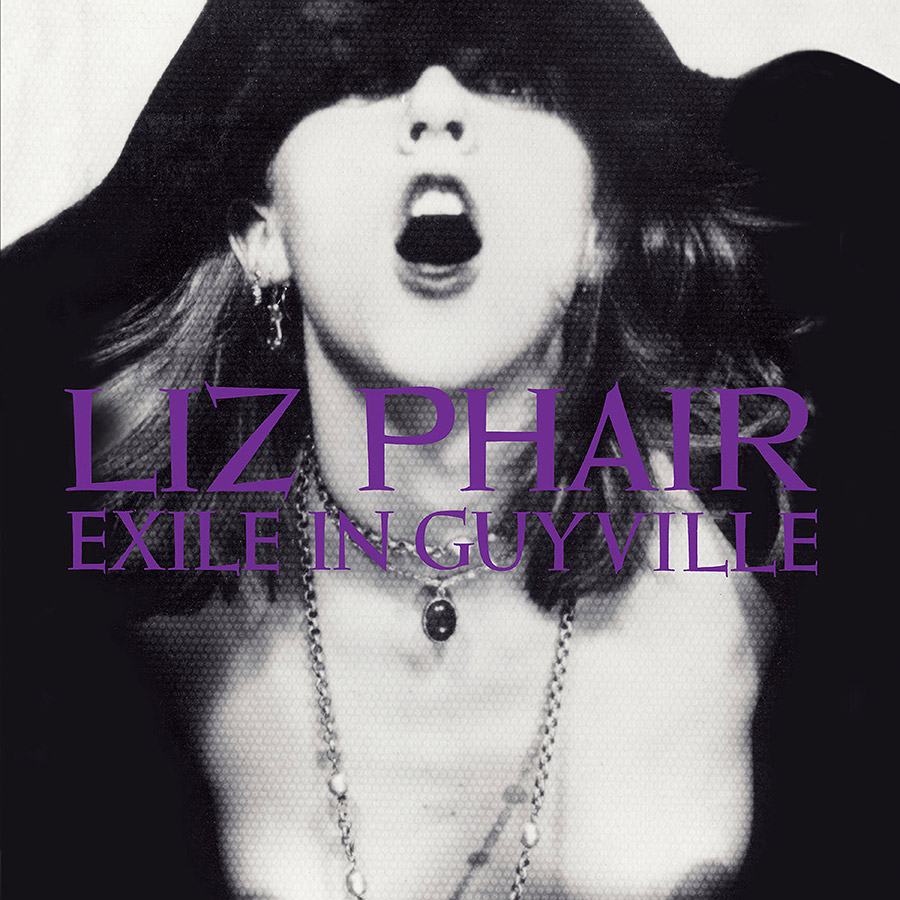

After the frazzled-but-fickle shamefaced lament of “Fuck and Run” (discussed last week in a special roundtable edition of Between the Grooves’ Exile in Guyville series), “Girls! Girls! Girls!” serves as both a musical interlude that helps usher in the record’s moody second half and also as a kind of response to the previous track, which left us — and Liz — with a sense of uneasy ambiguity regarding the implications of its aftermath. My guest commentators noted that “Fuck and Run” places important if somewhat subliminal, emphasis on one of Guyville’s major conceptual conceits: that Liz is enacting an ultimate act of feminism and rebellion by daring to do what the men are doing. Even if she doesn’t actually enjoy or feel good about it.

But “Girls! Girls! Girls!” makes the argument that she’s just fine with it and thriving. She’s just left the strange-in-the-moment but all-too-familiar “Fuck and Run” bed and is now making the immediate, conscious decision to be “cool with it”. She’s either progressed in record time, severely regressed emotionally, or she’s simply wavering, right on schedule — as we’ve learned by these close and frequent listens and examinations of her lyrics there’s always, for Phair, a sense of fluidity to emotion, esteem, and self-worth. She needs not take a stand or identify herself just now, if ever, with a sense of permanence; rather, she needs only to be true to how she feels in the wake of a particular encounter. And in this instance, she feels pretty assured.

“If I wanna leave”, she warns the Guys in the Ville, “you better let me go / Because I take full advantage of every man I meet”. This doesn’t quite sound like the Liz from 40 seconds earlier, crawling out of her skin in light of her predicament but also wishing her bedfellow would just fucking ask her to stay a while longer (and mean it), and yet this all makes complete sense. Rather than doing the proverbial “walk of shame” from her one-night stand’s apartment, she’s made an instant transformation, a decision to default to confidence and culpability, to take ownership over the situation, that tried and true self-defense mechanism that turns embarrassment into ego.

In crowning herself a maneater, she’s behaving in a masculine way, aggressively assuming the demeanor and mindset of her own aggressors before she can fall prey once again. “You’ve been around enough to see / That if you think you’re it / You better check with me”, she reminds her subject — but has he actually seen anything like her? Has anyone ever spoken to or treated him this way? Or is she simply aligning herself with how he behaves? Phair insists that she “get[s] away / Almost every day / With what the girls call murder”, but that sort of prowess and sexual conviction isn’t quite reminiscent of the voices of the previous ten tracks. “Dance of the Seven Veils” comes close, but that song’s hot-and-bothered-ness was still working towards the goal of keeping the object of her lust (and fury) nearby; on “Girls”, Phair seeks (or claims to seek) detachment, to clear the path for the space she promises she’ll need to take.

Musically, “Girls! Girls! Girls!” is one taut, stretched rubberband, a piece of sonic suspense that comes so close to snapping but never does. Phair speaks her vocals almost in murmur and the guitar — bouncy, bassy, nervous — matches the grayness of her tone. It evokes a sense of old Hollywood noir seduction crossed with the sensibilities of a Quentin Tarantino trailer. It’s fitting that the song would serve as a so kind of blue-balling, refusing to offer any sense of release as Phair expertly weaponizes her sexuality. What’s more, the title “Girls! Girls! Girls!” calls to mind sleazy marquees and billboards advertising “gentlemen’s” clubs, commodifying women, alerting men to their presence and availability with phallic exclamation points that double as directive arrows to the source.

But as whimsical or tongue-in-cheek as the track’s naming, it also enacts a kind of consistent failure on Phair’s part, a tendency to overstep the boundaries of her own awareness, of becoming one of the Guys as a means of subversion but soon forgetting herself and falling for their shit once again. This won’t be the last time Phair’s will is quickly broken (as evidenced in next week’s examination of “Divorce Song” and “Shatter”) or the last time she rebuilds and steels herself for a fight (future entries “Flower” and “Gunshy”). But after all, it is a woman’s prerogative to change her mind, right? And after all, aren’t they simply just taking their cues from men, whose shiftiness is rarely questioned and never subjected to trite idioms as explanations — or indictments — of their behavior?

12. “Divorce Song”

“The license said / You had to stick around / Until I was dead / But if you’re tired of looking at my face / I guess I already am”.

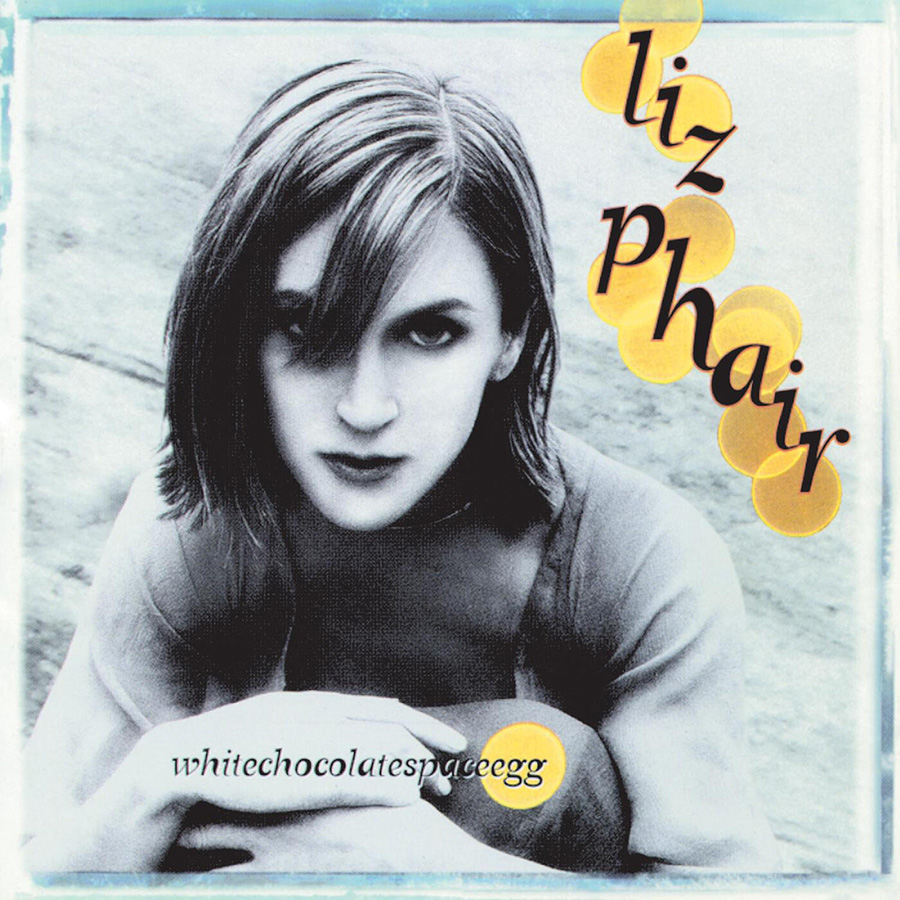

That Liz Phair could write about the Groundhog’s Day of twentysomething single-girlhood with the kind of verve and nuance that makes Exile in Guyville so inimitable, and so right-on remains an impressive, if not completely isolated, achievement—after all the early days of the ’90s also saw the likes of Tori Amos, Bjork, Ani DiFranco, and PJ Harvey changing the musical landscape. That Phair could write a song as hilarious and devastatingly poignant—and prophetic, it would later turn out—as “Divorce Song”, however, is a true testament to her gifts as a storyteller and keen observer of human behaviors, emotions, and the delicate imbalances in male and female perception that can send a once thriving relationship entirely off-course.

“Divorce Song”, another entry in the “domestic nightmare” branch of Phair’s catalog, employs the clichéd road trip scenario—all that time crammed into a hatchback driving cross country and getting on each other’s last nerve—that so often causes tempers to flare and hurtful truths to leak like engine oil, and unearths realizations about the extent to which each party intends to honor his or end of the presumed lifelong commitment. The road trip is, of course, an easy metaphor for the relationship itself, every aspect of what works and what doesn’t truncated into a successive, isolated sequence of moments that mirror the very best and worst of a coupling, an accelerated staging of the dooms that lie ahead. The great irony here is that it doesn’t quite make sense that sharing this particular space should bring out or exacerbate these qualities, that the seams should show more on this occasion than any other.

But Phair understands that, even in the most intimate of relationships, we still possess the urge to exert and hold onto our autonomy and the personal routines, habits, and perceptions that constitute said individuality. As the song begins, Phair explains that she “asked for a separate room” because “it was late at night / And [they’d] been driving since noon.” She thinks nothing of it, given that she and her Guy have spent an abnormal number of hours in isolation, already expending that stretch a couple would typically share side by side at night, asleep and not interacting, in a space similarly confining as the marriage bed. To impose that separation as they pulled over for the evening seemed to Phair not offensive but practical. But when she reflects back on the request, she responds with both regret and self-spite: “If I’d known how that would sound to you / I would have stayed in your bed / For the rest of my life / Just to prove I was right / That it’s harder to be friends than lovers / And you shouldn’t try to mix the two / ‘Cuz if you do it and you’re still unhappy / Then you know that the problem is you.”

The husband’s subsequent insensitivity proves far more vitriolic than hers, far more punishing and esteem-crushing. He lists off her minor failings—taking his lighter, losing their map—and then declares she isn’t “worth talking to”. That he uses her innocuous suggestion of separate sleeping quarters as an occasion to lash out in this severe way stuns Phair to her core, and we hear the quake in her voice as she scrambles to make sense of this false equivalency. This calls to mind, for Phair, how he’s set her up in the past for similar failure and ridicule, lamenting that “he put in [her] hand a loaded gun / And then told [her] not to fire it”, assigned her responsibilities and tasks and then “accused [her] of trying to fuck it up.” Despite his waffling and his effortless cruelty, Phair still promises that he’s “never been a waste of [her time] / It’s never been a drag.” “Take a deep breath and count back from ten,” she instructs, hopefully, pleadingly, “and maybe we’ll be all right.” Essentially, Phair has realized (or imagined) that even though the relationship has evolved on the surface, from the juvenilia of dating to the supposed maturity of marriage, the Guys in the Ville are engaging in the same old tricks, withholding opinions and feelings, existing in ambivalence Phair’s female voices have no choice but to interpret as everything being just fine, until that moment of such extreme, irreparable revelation. Had she fathomed what would have walked through the door she’d inadvertently opened, she certainly would have stayed in his bed and kept mum.

The song ends with a honkytonk-ish instrumental outro, evoking the image of someone either hightailing it out of town (has one of them left the other? Are they in the car together, continuing onward in their marital misery?) or maybe some raunchy makeup sex, since sex exists as both an equalizer and a demoralizer on Guyville, a creative and destructive force that plagues the women and men alike. Either way, we’re left not with an ending (there are still six more tracks) but rather the distinctive sense of an impasse. The car’s moving, but the characters in “Divorce Song” are very much standing still.

13. “Shatter”

Rarely does a song capture the essence of its imagery through its acoustics as effectively as “Shatter”. To describe and dissect with words Exile in Guyville’s most achingly beautiful track is to do it a disservice and enact a small betrayal of what makes “Shatter” so brilliant in its composition. It is Guyville’s most tender spot and its longest by nearly two minutes, thanks to the song’s hypnotic, meandering opening instrumental, that signature echoing-jangle of Liz Phair’s perfectly imperfect chord work rising and falling against a tremulous bass line that evokes both an urgency and a slowing.

“Shatter” begs to be experienced on headphones, safe from outside distraction, its listener’s eyes closed, body in recline, as vulnerable and receptive to its musical and lyrical impact as possible: the feeling of the summer breeze in your hair; the dark highway insufficiently illuminated by headlights; the shallow, contemplative breaths that both remind us of our solitude and mirror the track’s minute but wrenching movements. And while “Shatter” fits the trajectory of the Guyville narrative, it also deserves to be heard in isolation from the rest of the album, for “Shatter” is quite cinematic in its scope, its steady and sustained intro providing the kind of tonal encompassment requisite of any great film score.

Phair asserts that she doesn’t “always realize / How sleazy it is / Messing with these guys”, though we’re unsure if she’s doing the messing or being messed with. At this point, though, it’s safe to assume it an either/or scenario, as Phair has made as many grievances as she has confessions throughout Guyville, and trying to peel them would prove futile. What matters here is that there’s something clear but unnamable about the “you” of “Shatter” that “slapped [her] right in the face / Nearly broke [her] in two.” Phair’s delivery tells us this experience is, despite her choice of words, a gentle one, and the metaphorical violence is that of crushing affection rather than the patterns of critique she’s previously experienced. “It’s a mark,” she tells him and us; she will carry “for a long, long time”. And instantly, we understand that, despite how she feels, hearts have already been, or are in the process of being, broken—the suggestion quite strong that Phair is, for an unhappy change, the perpetrator in this instance. That she’s singing so softly, in her distinctive near-hum, in the past tense clues us in that she’s in the act of putting distance between them even before she subsequently delivers the crushing lyrics that confirm it.

“I don’t know if I could drive a car / Fast enough to get to where you are,” she laments, “Or wild enough / Not to miss the boat completely.” The risks she’s describing here are, of course, not literal but emotional. The notion of contemplating recklessness, of succumbing to a sense of abandon as a means of connection is extended in the form of an even more complicated vessel: “I don’t know if I could fly a plane / Well enough to tailspin out your name / Or high enough to lose control completely.” The move from car to plane is key; as she’s rationalizing her inability to make it work, she must impose this analogy in order to convince him that she isn’t confident enough or equipped to rise to the occasion.

She buttons these ponderings on the likely dangers and disappointments her time in Guyville has taught her to anticipate, no matter how appealing the prospects, by sing-sighing, “Honey, I’m thinking maybe / You know just maybe.” This is the ambivalence she’s learned along the way, and though we can hear her inherent resistance to it, can feel that at her core she wants to take the plunge, to lose control and give herself over to the possibility of things being different this time, there’s ultimately a scarring mistrust—in him, in herself—that she cannot escape, that she must consider every bit as profoundly and knowingly as she does the way she feels. Resolution, it seems, can come only from removal, and so she makes the heart-heavy decision to do so.

“Shatter” is one of many tracks on Guyville in which the title never appears in the body of the song itself, an invitation by Phair for us to decipher how it might fit into the puzzle. Here, “shatter” seems to reflect the notion of a weakening, an impairment. This Guy has abruptly, momentarily shattered the cynical expectation that Phair has cultivated that these men will always shatter any expectation she holds them to, a terrible cycle of damned-do’s and don’ts that will ultimately reward and satisfy no one. The man in “Shatter” has managed to break down her resolve, but in the end, her faith has perhaps suffered too many knocks for her to see it through.