By Dwight Garner

The New York Times, June 19, 2014

Frank Zappa made a hobby out of tilting at rock journalists. He called the lot of them, in a tidy summary, “people who can’t write interviewing people who can’t talk for people who can’t read.”

Zappa would probably find a reason to dismiss the book series called 33 1/3, issued by Bloomsbury — after all, it doesn’t yet include a volume about his work. For the rest of us, though, the series is probably the most remarkable regular event in rock journalism today. Each thin volume — there are nearly 100 of them now, enough almost to stretch across the back seat of a Mini Cooper — presents one critic on one album. A lot of these writers are capable of shredding.

Gina Arnold’s new book takes its name from, and chews over, Liz Phair’s wise, weird, lo-fi, high-concept and flat-out beautiful 1993 album “Exile in Guyville.” This is easily among the best books in the series thus far. It’s the most curious, for sure.

Ms. Arnold omits most of even the most bedrock facts about Ms. Phair and her album, leaving the finicky details to Wikipedia and to magazines like Spin, whose oral history of the making of the record is a treat. Don’t come here to discover who engineered “Exile in Guyville,” or how the songs came to be written, or what was on the recording studio’s walls. There’s not enough biographical info about Ms. Phair to cover one side of a debit card.

Instead, Ms. Arnold, a rock critic whose previous books include “Route 666: On the Road to Nirvana” (1993), hijacks Ms. Phair’s album and, like a late-night disc jockey adrift on a pirate radio barge, uses it as a platform to rap about a dozen other things, including the death of rock criticism, the end of a certain crucial indie sensibility and third-wave feminism. She also extends Ms. Phair’s critique of the belittling masculinity of alternative music culture.

This is free-form criticism, and Ms. Arnold occasionally darts her way into sticky corners. She has a fondness for academic patter and too often, for example, drops the word “privileges” as a verb. I’m not sure that comparing Ms. Phair to Frantz Fanon adds anything to the sum total of human intelligence. If you are going to go out of your way to describe what Mick Jagger looks like onstage, the lowest hanging fruit in the orchard, you’ve got to do better than “He reminds me of a spastic spider crossed with a rabid fly.”

But for the most part, I found this book to be, like Ms. Phair’s album, charming and brave and unexpectedly moving. The author is excellent on so many things, including how the power of Ms. Phair’s songs grows from their grainy details, quotidian observations that other rockers so rarely give us, about things like housework and roommates and “what is was like to feel voiceless and powerless in a nightclub, on a road trip, or during sexual intercourse.”

Ms. Phair’s album was a song-by-song response to “Exile on Main Street,” the Rolling Stones’ 1972 LP. There was wit and nerve in pushing against this most classic and casually macho of all classic and casually macho rock albums.

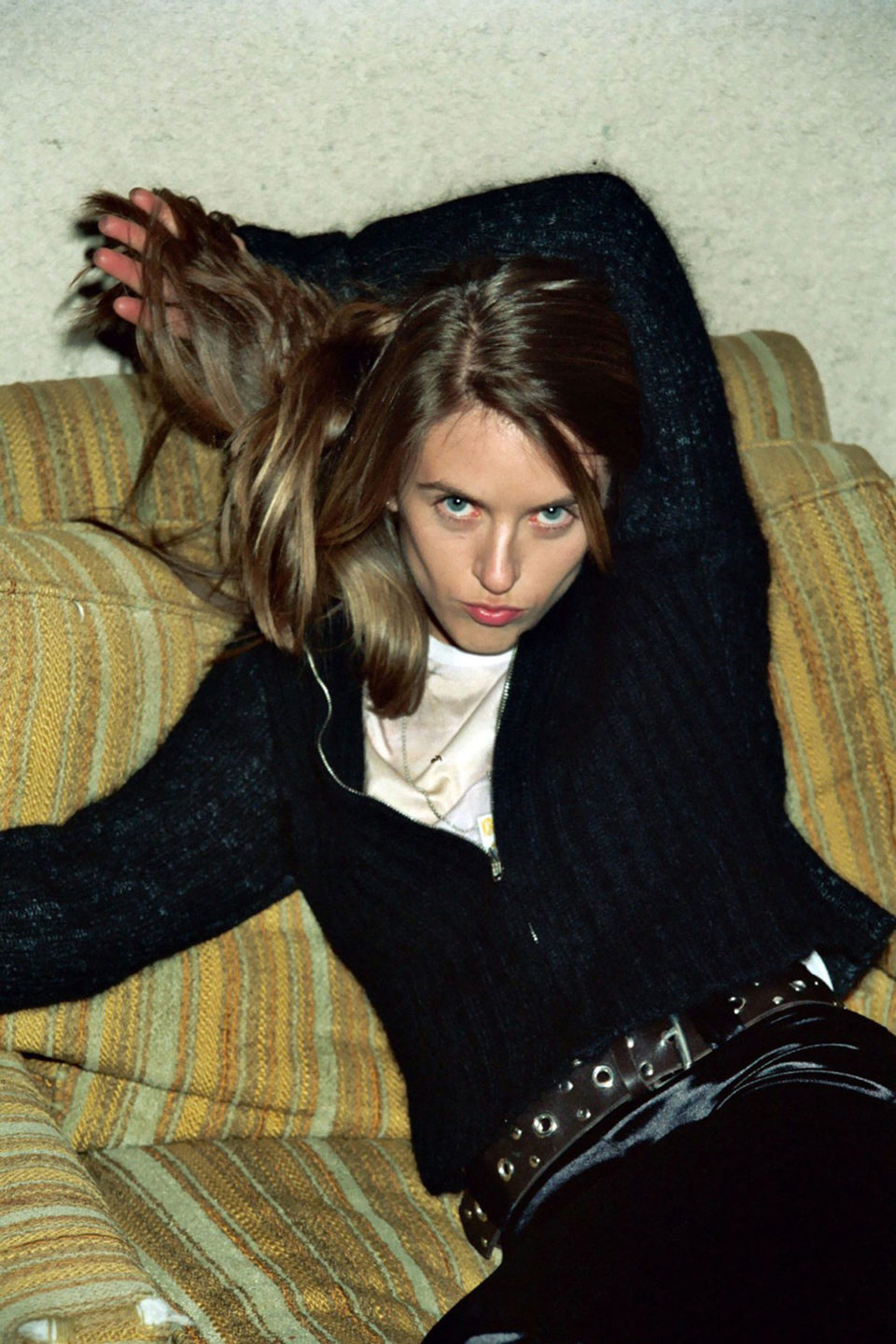

Most critics admired “Exile in Guyville,” if grudgingly. Yet Ms. Arnold charts the backlash that soon set in. Ms. Phair was found by some to be inauthentic, a limp noodle in concert, an untalented guitarist and too conventionally pretty — “the Brooke Shields of indie pop,” as one observer snarked. Ms. Arnold gives a striding tour of the casual sexism Ms. Phair endured, and she takes the long view: Making a masterpiece is the best revenge.

Ms. Arnold’s book functions as an elegy for a bygone age, one she labels as the space “between the eras of punk rock and Napster,” when both she and Ms. Phair were in their 20s, and rock critics were indie culture demigods. They seemed to be, at any rate, before the author grew up and consumed what appears to be a double shot of Walter Benjamin and Marx.

“Looking back, I am ashamed now to recognize how blind I was to my role in the cycle of music consumption: Every band I went to bat for, every flame war I took part in, every word I put to paper was simply a ka-ching in a cash register that I had no access to,” Ms. Arnold writes. She adds,: “In the end, all my passion and vitriol got replaced by apps that say, ‘If you liked that, then you may like this.’ ” She’s no enemy of the digital music world, but she can’t help but observe the wreckage that has attended its arrival.

The beating heart of Ms. Arnold’s book is an examination of Guyville itself. It is, or was, a real place — the Wicker Park neighborhood of Chicago in the early ’90s, a few blocks filled with coffee shops, scruffy bands and ardent audiences, where alt-weeklies and fanzines blew around like tumbleweeds.

Guyville was more crucially, she argues, a state of mind, though perhaps not anymore. Other, newer Wicker Parks exist, of course, but: “Guyville lies in ruins, wrecked in part by digitization, and in part by a culture that outlived its usefulness. Guyville is gone, and this book will be its memorial.”

There’s plenty to mourn about this lost utopian world, when you had to see a band live, instead of Googling its YouTube clips, and when buying a record was an act of almost blind faith — you couldn’t stream the thing first. Less worth mourning, Ms. Arnold observes, is how marginalized women were, relegated to being at best publicists or bass players, almost never record label owners or engineers. “Phair’s record brought out,” she writes, “the uglier side of the indie rock scene.”

Greil Marcus has a piece, worth finding, on Ms. Arnold’s book in the new issue of The Believer. This book sent him, as it did me, racing back to listen to “Exile in Guyville.” About it, he writes, “Arnold is betting on the right horse.” Mr. Marcus admires the album’s raw, strung-out quality: “That fatigue, that sense of being too tired to care but too blasted not to, gives what Phair did an odd realism that, in her place and time, no one else seemed to know was there, or to want to know.”

Listening to the record again herself, Ms. Arnold acknowledges (Zappa is smiling here) the limitations of writing about music: “You can do whatever academic exercise you want on the stuff, but in the end, you’ll never really be able to convey the power and beauty of a chord change, or why a particular record resonates.”

The haunting final words on Ms. Phair’s album, however, speak to a quality that’s so apparent in Ms. Arnold’s book: “I only wanted more than I knew.”