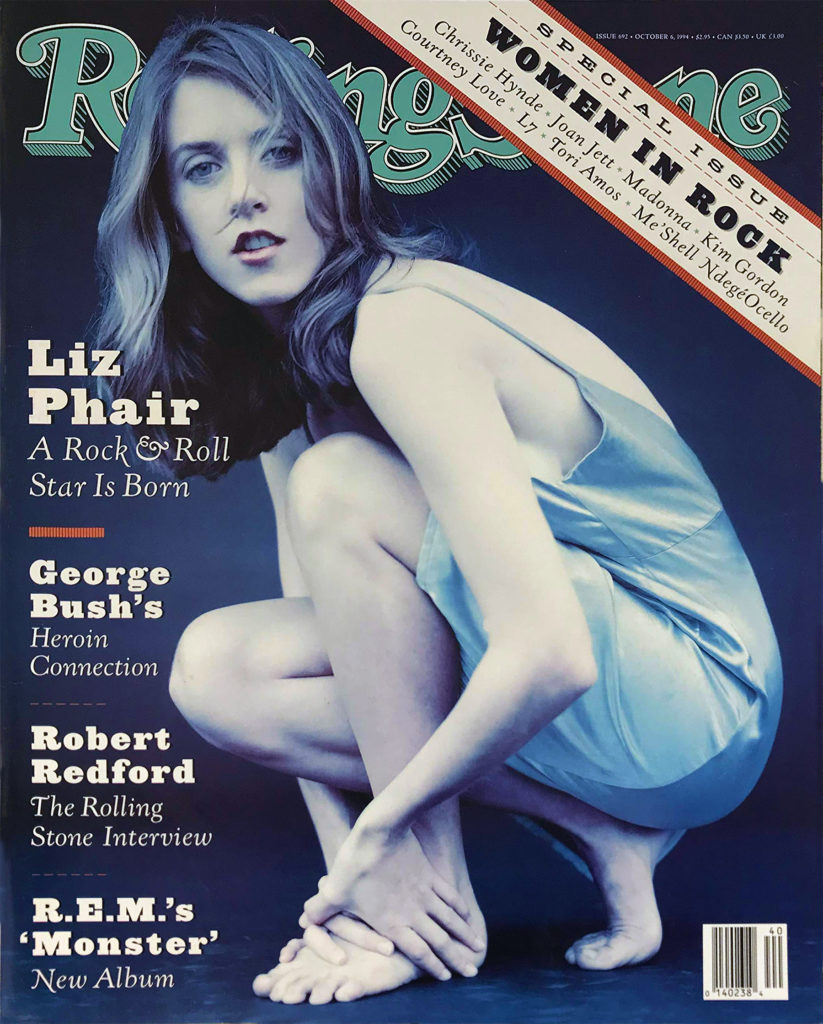

By Jancee Dunn

Rolling Stone, Issue #692, October 6, 1994

Liz Phair is doing her damndest to get past the security guard. “Pleeeease?” she wheedles as a particularly simian man blocks her way. “What’s the big deal, hmm?” She bats her eyes at him, giving him the full-on Phair charm, but the guard, meaty arms crossed over his barrel chest, is unmoved. “Sorry, miss,” he says a tad too happily. “The show’s already started. Can’t let you in.”

The show that will not grant Phair entrance, let alone backstage privileges, is not Woodstock ’94, nor is it Pavement, whose Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain Phair, 27, often jogs to. It’s not even the Rolling Stones. No, it’s slightly more alternative: It’s Coral Reef Dreaming, the nature movie playing at Chicago’s Shedd Auditorium. She strains to look past the guard’s Refrigerator Perry-size shoulders and tries another let’s-all-be-adults-about-this grin. The fact that Phair’s normally oratory powers are a bit dim doesn’t help matters — earlier, she and her companion got baked, high-school style, in the parking lot. “All right then,” she tells the guard haughtily as she spins on her heel. “We’ll look at the fish.”

We shamble over to the Animals of Warm Fresh Waters and commence two hours of pot-addled fish gazing. Scintillating dialogue ensues along the lines of “Look. Look at that one. It has a wart on its nose. Ha.” And “Check this little guy out. See? He’s smiling. See?” We lose steam near Animals of the Indo-Pacific and head back to the parking lot. She sees a look of doubt pass over her visitor’s face as she reaches for the keys. “I’m fine,” she says with a soothing tone in her voice. “Just get in the car.”

Phair pulls out of the lot… and smack into six lanes of traffic barreling head-on towards her blue Toyota Corolla. Isn’t it funny how life works out? I’m going to die here in this car with Liz Phair. She seems like a nice enough person. There are certainly worse ways to go. “Fuck! Fuck!” yells Phair as she throws the car in reverse and stomps on the gas. We shoot back into the parking lot and gulp a few deep breaths.

“Usually I’m a great driver.” She grins shakily. “No, I’m serious.”

FOR ELIZABETH CLARK PHAIR, THE PAST YEAR has been a similar rush of adrenaline. Seemingly appearing out of nowhere, the then 26-year-old bestowed Exile in Guyville — the demos of which were recorded on a four-track in her Chicago bedroom — upon a been-there-done-that world in 1993, which caused an instant furor, selling more than 200,000 copies, phenomenal for an indie-label debut. It’s debatable as to what element of Guyville received the most attention. Was it the fact that it was one woman’s 18-song answer to rock’s Holy Grail, the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street? Perhaps it was that the word guyville, lifted from a song by her pals Urge Overkill, was a retort to the sometimes stifling Chicago indie-music scene?

Could be. But likely it’s that Phair’s lyrics were, to put it mildly, not for the timid. Lyrics that gave new meaning to the question “Can I be frank for a moment?” Lyrics that brought forth a collective ooh-weee from a titillated rock press, which seized upon her generous use of the word fuck and phrases like “I’m a real cunt in spring/You can rent me by the hour” and the oft-repeated “I want to be your blow-job queen.” Heady stuff for a girl hailing from a wealthy Chicago suburb.

Whatever the reason, indie-rock gurus buried her under a landslide of praise (New York’s astute if over analytical Village Voice named Exile Album of the Year for 1993, the first time a woman had captured that honor since Joni Mitchell reigned in 1974, when Ford was in the White House), which means that all eyes — no pressure here! — are eagerly cast upon Act 2, Whip-Smart. As it turns out, the new album is a stunner — and, dare we say, better than the first — a perfect progression from Guyville, carrying over all of the DIY feel of her first offering but with greater accessibility and tighter arrangements. “The first album is for Your People,” says Phair. “The second is for the People; the third is for Everybody. Your People hate your second album because it isn’t for them, but you have to get the attention of the People, who will get a sound, get an idea, digest and spit it out. And the next time you can get revolted by that and go back to the original Your People mentality, which is more intimate.”

On Whip-Smart, Phair once again unflinchingly examines the rocky terrain of romantic relationships, but on this go-round, a notable thread snakes throughout the lyrics: gender reversal, a subject that has been on Phair’s mind as a result of being in a serious relationship for more than a year. As for the album’s sound, Phair’s guitarist, Casey Rice, says it’s “more rocking. It sounds more like a band record than a studio record.” Bass player LeRoy Bach agrees. “The new album is a lot better than the first. Better songs, less what would be rambling, introspective, self-indulgent things.”

And again, Phair has complete control of the project, from cover art (“It’s a Russian constructivist propaganda poster”) to production (assisted by her drummer, Brad Wood) to the video for the frothy guitar pop of the album’s first single, “Super Nova,” a jubilant salute to a lover’s prowess. Phair will be sitting in the director’s chair.

Which brings us, on this sun-dappled day, to the Bank, home of Urge Overkill’s Blackie Onassis and general headquarters of the band. The Bank, a gutted structure in the slightly seedy Chicago neighborhood of Humboldt Park, is a decadent, cavernous place — very Vincent Price. It’s a custom-made setting for the video shoot, which is about Phair’s current obsession, the supernatural.

A propman lugs in a stuffed owl, which blends in seamlessly with the surroundings. The director is simultaneously applying makeup to herself and issuing directions. “The lamp needs to flutter more,” she tells a techie. “LeRoy,” she tells her bassist and video star, “as it flutters, you look at it like ‘What the fuck?'” Phair, clearly in her element, is enjoying herself immensely.

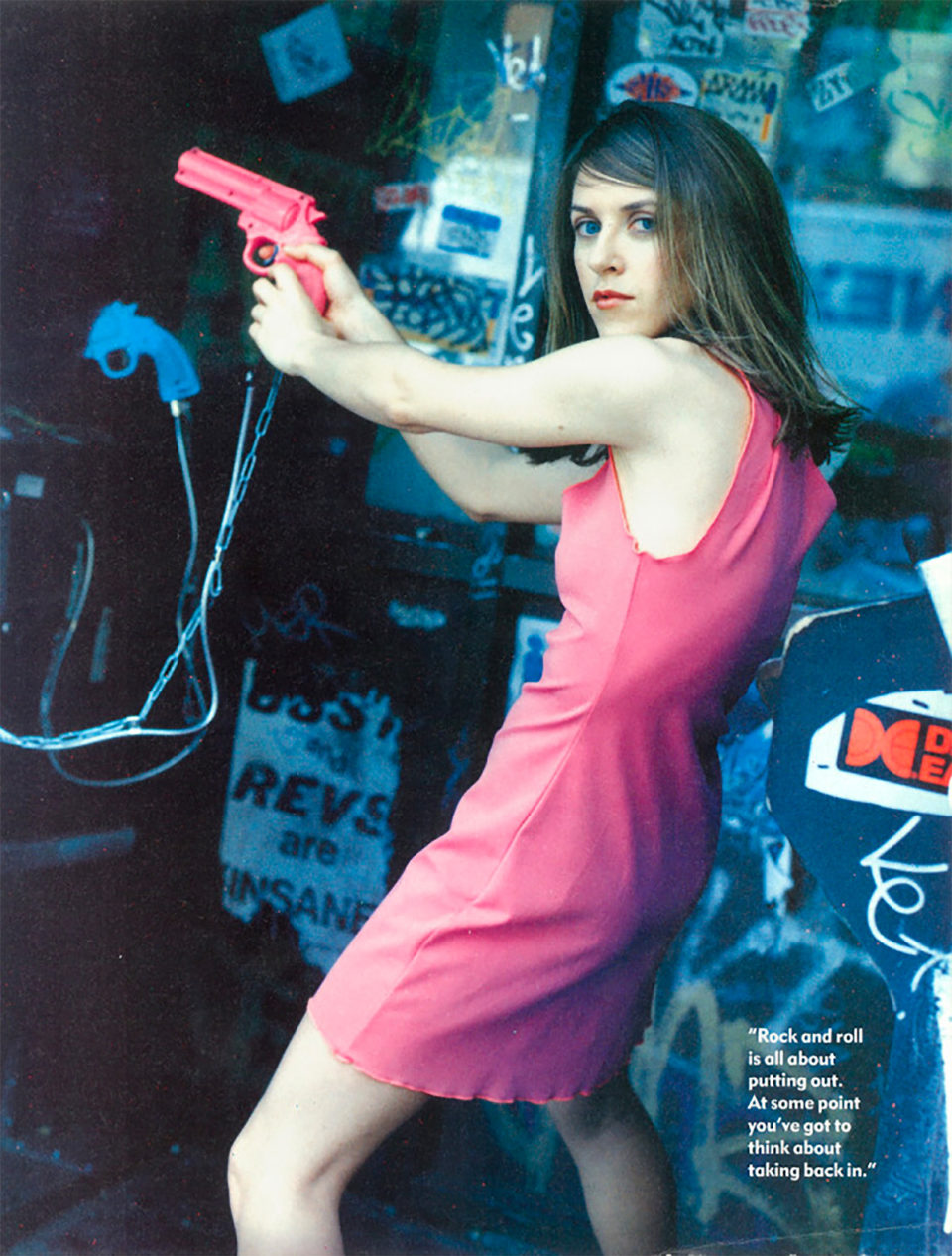

“I’m just nuts about ghost stories right now,” Phair says on a break. “Maybe because entering the rock world kind of bashed a lot of pop-culture illusions I had. It was the last bastion of mystique for me as a kid.” Up close, Phair is petite — your grandmother would call her a slip of a girl — with enormous blue-green eyes and clean, tawny skin. Contrary to her lyrics (and her shiny pink dress), her sexual presence doesn’t reach out and grab you by the lapels; instead, she radiates a low-grade sexuality (or is it confidence? or both?). She laughs easily and often and punctuates her speech with improbable phrases like “You retardo!” She talks swiftly, purposefully and articulately, with an easiness suggesting that this is a woman who views conversation as an art form. She is genuinely interested in what she has to say and is stimulated by the things that come out of her mouth.

Phair is also hyperobservant, prone to near-obsessive analysis. “I grew up in dialogue,” she says. “My family table always had discussions that ended up in verbal wars. Whenever the extended family came over, it was sort of a verbal power play. I remember being a young girl at these tables with my dad and my male cousins and my uncle, who was very loud. I didn’t know anything, but I wanted to talk really loudly.” It’s easy to picture her theorizing at a coffeehouse, arguing late night at a bar about politics, the male-female dynamic, art vs. commerce. Hell, about Astroturf vs. grass. “Let’s talk about Cher,” she announces at one point before launching into a discourse that is as damned stimulating as it could possibly get about a woman who shills for Lori Davis Hair Care Products.

Phair’s analysis, however, extends to her own work. There is a calculated veneer to her dissection of her own albums — so much so that at times they seem more like a college thesis than like music. Phair has denied that she manipulates the media, but her keen awareness of the music machine and her deconstructive tendencies point to a different conclusion: She is all too aware of her role. “You’re there to be a salesperson, a model spokesperson,” she says about the music biz. “It’s consumerism.”

Phair has thrown herself into all things occult for this video. “Oh, man, I went to graveyards, haunted houses, I quizzed everyone I knew,” she says. “I’m really into it, because the phenomenon itself is never any less interesting for the mind to play with than things like astrology or birth and death or mythology.” She says these interests are decidely female. “I’m always reawakening and realizing I’m not a guy. What I really like are things like intuition, freaky experiences, coincidences, fatalism.

“I believe in ghosts,” Phair says. “I used to think I was a witch when I was little. I had a lot of magic in my life when I was a kid. And I refuse to lose it, because it isn’t something that was just a game. It was how I knew my place in the universe.”

PHAIR’S UNIVERSE WAS FERTILE TERRITORY for a bright, inquisitive child. She was adopted at birth by a physician father (he’s chief of infectious diseases at Northwestern Hospital) and an art-instructor mother (she teaches at the Art Institute of Chicago). Phair will not be embarking on a quest for her birth parents. “The only thing the adoption did was make me feel a little more liberated from my background than most people,” she says shrugging. “I can invent my own legacy, because I don’t really have one.”

Phair was raised in the upper-middle-class suburb of Winnetka, Ill. (Lest a visual picture need be painted: Remember the house where Ferris Bueller took his day off? That was in Winnetka.) It was a galaxy far, far away from the angst-ridden upbringing of your stereotypical rock star. Phair’s parents were nurturing and supportive. “They loved me to death,” she reports. “Maybe because I’m adopted, they didn’t want to mold me. They encouraged me, they were interested in me. I always had a weird net of safety around me.”

Phair is seated at a picnic table outside the Lincoln Park Zoo. It’s late afternoon, and a balmy, animal-scented breeze lifts her hair. Pressed for dirty laundry, she says, “They’ve got a little bit of WASP, appearance-oriented, academic prejudices, stuff like that. In a way, it’s not a normal cross section of a family.” She has an older brother, also adopted. She went to summer camp with Julia Roberts (cited in Whip-Smart‘s “Chopsticks”) when she was 13. “She was tall and bossy and fun. I always had tall, bossy friends.” Alas, the friendship waned. “We stopped speaking because she was always calling me collect, and it pissed me off. I’m like ‘What are you fucking calling me collect for? Your parents are rich enough.’ She only did it a few times, but she was enough of a power player. Tall, bossy friends get you in the best kind of trouble, though.”

In high school, Phair endured an awkward stage, but it passed. “I got my glasses and braces off and got my hair cut. Suddenly I was like ‘Hell, yeah! I can do this!'” Transformation intrigues Phair — it’s a subject that also touches on a strong fear of disfigurement that began in her early years. “Because my father’s a doctor, I’ve always known about the foibles of the body,” she says. “I had access to those medical textbooks.” Two images in particular terrified Phair — before-and-after shots of a boy with leprosy. “In one picture he looked cute in a teen-age way, standing there, bored. Next to him was a picture of him a year and a half later, and he was a monster, a freakish thing. You could see his eyes in the first portrait, and to think those same eyes were there in the second portrait — it freaked me out.” Throughout college, Phair’s art projects consisted of charcoal drawings of diseased faces.

Phair’s original calling, in fact, was art. At Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, however, she walked into a thriving band scene. Bands from there that went on to greatness (and near greatness) include Codeine, Bitch Magnet, Seam and Come. “Everyone had a band,” says Phair. “It was exactly like Chicago — in fact, a lot of them moved there. There was a lot of rock & roll spirit, but it was an intense place. Neurotic overachievers who want to be hip.” It was there that she began writing songs.

Chris Brokaw, Come’s guitarist, first met Phair at Oberlin but grew close to her on a jaunt to San Francisco, where Phair had drifted after college. “I was visiting a woman she was rooming with,” Brokaw says, “but I ended up mostly sitting around playing guitars with Liz. I had been sort of unaware that she played or wrote songs. Then she plays me these amazing tracks. I think one was called ‘Fuck or Die,’ and one was ‘Johnny Sunshine,’ which ended up on Exile in Guyville.”

When Phair decided to head back to Chicago, Brokaw urged her to make him a tape. “A couple months later she sent me this tape of 14 songs that she had done on a four track, then a month later, she sent me 14 more equally amazing songs.” The tapes, dubbed Girly Sound by Phair, began circulating on the East Coast underground tape scene. “I started telling people, ‘I’ve got this friend named Liz from Chicago, and she’s like the great new American songwriter,'” says Brokaw. “Everyone was like ‘Yeah, yeah.'”

Phair, who has been making up songs “since I was little,” will not release the tapes anytime soon. “I go in there and rip stuff off — it’s like a library,” she says. “There’s about 50 songs. A lot of it is juvenile cleverness. There’s verses, there’s choruses, there’s subchoruses. It just goes on and on. There’s a certain naive sound, more breathy. It’s more me.” Nonetheless, the collection proved enough of a treasure trove to pique Matador Records’ interest, which nabbed her in the summer of 1992. Exile in Guyville was soon under way.

In the studio with her drummer and co-producer Wood, Phair let drop the idea of a female answer to Exile on Main Street. “When she first brought it up, I was like ‘Oh, really? You mean you can’t get into that album like I do?'” says Wood. “Because it is a real guy thing. Her logic started to make sense.” The result wasn’t so much a song-by-song response to the Glimmer Twins’ he-man posturing — it was more in the songs’ sequencing and thematic content. Phair and Wood’s low-fi production was entirely on purpose. “We didn’t want it to sound like a retro record, and we didn’t want it to sound real ’90s,” says Wood. “I wanted it to sound really personal, trademarked like the Stones record sounded, so that as soon as you heard a note off it, you said, ‘That’s the Rolling Stones.'”

Wood and Phair succeeded, aided, of course, by Phair’s remarkable lyrics — an intimate, conversational meld of longing, sex, strength, power struggles, asshole guys and humor — sung in a voice that isn’t entirely different from Everywoman’s. Beverly Sills she’s not, but that’s OK. Phair does nothing the conventional way — she deliberately didn’t fall within her given range, didn’t bother with traditional song structures (she has a legendary aversion to verse chorus verse) and didn’t even attempt to play traditional guitar chords. “She just comes up with goofy chords because she makes them up herself,” says Wood.

“People never talk about her guitar playing,” says Bach. “But she’s brilliant on guitar. The work that she puts into this shit is not discussed like someone else’s work method might be discussed. She does a lot of normal things that famous guy musicians do, but that’s not part of the Liz Phair conception.”

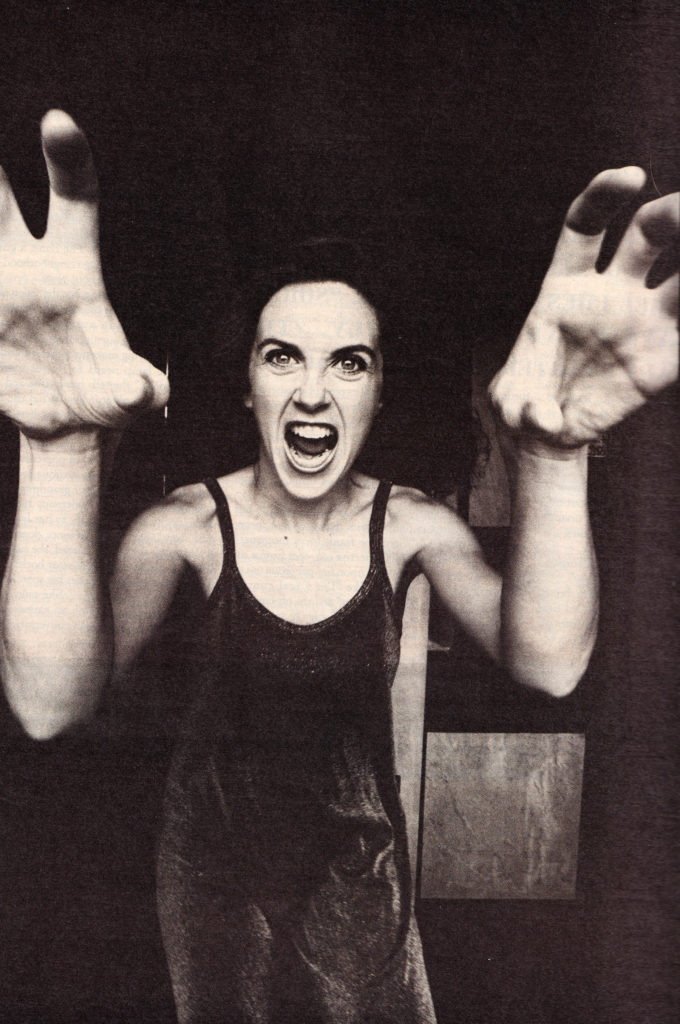

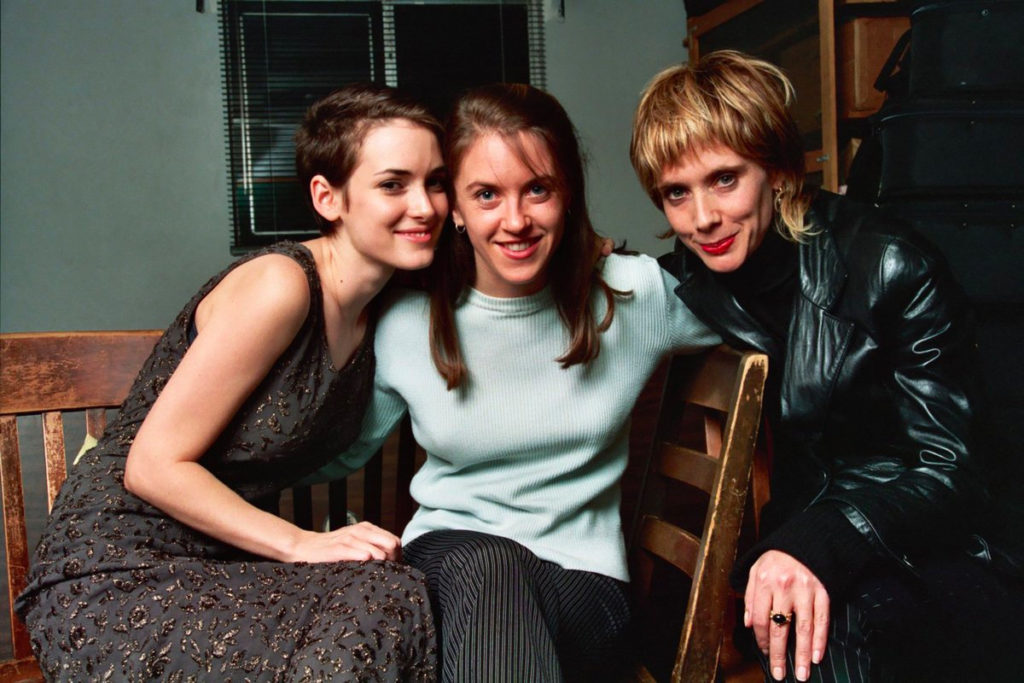

The conception started forming in mid-1993 when Guyville was released. Critics were beside themselves (picture the Chimp Gone Wild scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey and you’ll get the idea), heaping her with accolades and comparisons to Polly Harvey, Chrissie Hynde and Madonna. Rock scribes were less kind when Phair faced an audience, something she had never done in her life. At early shows, she suffered from debilitating stage fright, which made her voice crack like a 13-year-old boy’s. It didn’t help matters when famous faces started dotting the audiences at her shows. (“God, I was so tongue-tied when Winona Ryder and Rosanna Arquette came to one show,” moans Phair. “I was a complete dweeb.”) Although she used to claim that she would never attend one of her own shows, she seems, lately, to be conquering her fears. “I actually enjoy myself onstage now,” she says, although she hasn’t yet seen her tour schedule out of “total avoidance.”

What calmed Phair were the adoring faces, especially those of women, in the audience. “It’s weird, though, when 12-year-old, cute, happening girls want to be introduced to me, because talking to me would be a coup,” she says as she walks toward her car. “The objectification of your person is very bizarre. You become the same thing as the right pair of shoes.” Still, droves of other women are die-hard fans, quaveringly asking for hugs backstage, whispering that she has saved their lives, mouthing every word to songs like “Fuck and Run” (“Whatever happened to a boyfriend/The kind of guy who tries to win you over?”) and “Flower,” with lyrics that would make Rick James blush. (“Every time I see your face/I get all wet between my legs.”)

A word here, if we may, about the flurry of attention Phair has received due to her strident focus on her naughty bits. She rightly maintains that her songs are directly reflective of conversations that most young women are having across this great land right now and that those chats are as frank, casual and often clinical as those of men. “It scares guys,” she says cheerfully. “I’ve had more male friends freak out.”

Phair has been accused of being a shockmeister, using sexual bluntness as an attention-getting device both in her lyrics and in her conversation. She’s certainly not shy. “Women dissect,” she says. “About giving blow jobs, for example — you talked to your friends like ‘What are you supposed to do? Where? How do you know if he’s going to come?’ Then women will have really sexual names like ‘old purple dick’ or something.”

THE BLUEBERRY PANCAKES HAVE JUST arrived at the Bongo Room, a favorite Wicker Park hangout with an earthy, crunchy feel. There is a problem: “The blueberries are on top of the pancakes,” Phair tells a waitress. “I want them in the pancakes. I eat here all the time. They have never been on the pancakes.” The offending flapjacks are promptly replaced.

The subject of sex comes up, as it is wont to do. Phair has been keenly aware of her sexuality since she was young. Her earliest erotic memories were triggered by the illustrations in Alice in Wonderland. “Can I confess something really gross?” she says. “Those men were slightly erotic to me. The skinny legs, the big noses. I don’t know.” She also got an unexplained charge out of “Darth Vader, big time. Until he had his head taken off.” Mr. Green Jeans (Captain Kangaroo’s neighbor) also provoked a reaction. “He was such a peripheral character,” she says, analytically, waving a fork. “There was something about him. Kinda quiet, always doing something. He was the male, busy like Dad, but he had the time to come fuck you.”

Phair’s personal supernova is Jim Staskauskas, a film editor and her constant companion of more than a year. The two met when he edited her first video, “Stratford-on-Guy.” Phair had a dual reaction to him: “I’m thinking, ‘Who is this dick?'” she says. “He had the whole editor, bigger-better-older-than-you thing going. But I also had an immediate physical reaction to him. I don’t get those reactions anymore.” Staskauskas, a genial regular Joe with his girlfriend’s coloring, took his time asking her out (“He played me like a goddamn fiddle”), but now the two are inseparable.

Phair, in fact, is primed and ready to get married. She may be part Marilyn Chambers, but she’s also part Sandra Dee. “I’m up for it,” she says with gusto. “I don’t see marriage anymore as the end of my life. It’s not a step down, it’s a step over.” She shrugs. “It sounds exciting.” She has the scene — who knew? — fully envisioned, complete with dress and a small ceremony by the beach. Staskauskas is more cautious, having been married before and being the father of one 15-year-old son named Aidan. The three live together in an apartment in Wicker Park. “It’s weird for Aidan, and it’s weird for me,” Phair concedes. “But luckily, we get along.”

Phair’s relationship has had a measured effect on her writing. “The whole attitude of Whip-Smart is affected by him, affected by my new way of seeing myself,” she says as the Bongo Room’s proprietor stops by to say hello. “But I really couldn’t say. I’ve never been able to write about people. In fact, I wrote some songs that were directly about him, and they didn’t make the album.” One tender love song “came out sounding like Don Ho. It was supposed to be the ultimate light-rock Carly-forever love song, and here I am making, like, ‘Tiny Bubbles.'”

Surprisingly, Phair says she doesn’t often write about people she’s involved with, which begs the question: Wasn’t one specific former relationship addressed on Exile in Guyville? Phair has been cagey about this in interviews. Pulling an answer out of her recalls the Whitewater hearings. “I tend to write more about imaginary scenarios,” she says carefully. “Or scenarios that aren’t actualized but could have happened. In a way that’s my infidelity. Or I code them up, so that only the people that I want to hear them do. It’s like a little secret garden.” Meaning Guyville was not about one person? “It’s not that simple. I answer this a lot of different ways, because I don’t want it to be known one way.” She pauses and fiddles with her napkin. “That situation just naturally defused. It was never real in some way. That’s why I could write a whole album about it.” It, meaning one person? “It just pulled out of focus, and my life changed. You can have personal tragedy and not remember it very well in five years.” All righty. Meaning you had a personal tragedy with one person? “I did Guyville for myself, because I wanted him to know who I really was.” Phair 1, interviewer 0.

“I HAVE TO WARN YOU, I HAVE A RAT,” Phair says calmly as she rounds a corner on two wheels of her car. So call an exterminator, her companion suggests helpfully. “It’s a pet,” she says. “It’s actually cute. Honestly. Yes, its teeth look like staple removers, but it’s in a cage. His name is Willard.” We’re on our way to her house after breakfast. She blithely heads (honest to God) the wrong way down yet another one-way street. A vast collection of McDonald’s cups in her back seat shifts with the direction of the car.

As she bursts into the kitchen, the phone is already ringing. Aidan is home, but he is sleeping, teen style, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. She checks in on Willard, who is also asleep, in what appears to be a three-level rat condo. The apartment is not particularly rock & roll — except for the bathroom reading: The Encyclopedia of the Occult. Instead, it’s a cozy domestic nest for Liz, Jim, Aidan and Willard. Phair settles into a couch. “Life got a lot more open-ended for me lately,” she says. “I thought that once you hit adulthood, you settled into your mode. It’s not really true. It’s almost a reincarnation. It makes me believe in reincarnation, because if you can shift as much as you can in a lifetime, I don’t see why you can’t shift as naturally after a lifetime.”

Phair says her lyrics in the new album’s title track are “kind of like the values that I recently reaccepted into my life. Whip smart is something that I respect in people. It implies education through trial, an attitude I like. Exile in Guyville was a more sexual album. This is the opposite, an emotionally based album that ended up being more sexual.”

To the point where Phair appropriated Staskauskas’ role by the end of the album. “I made a rock fairy tale,” she says. “A little myth journey — from meeting the guy, falling for him, getting him and not getting him, going through the disillusionment period, saying, ‘Fuck it,’ and leaving, coming back to it.” There is a real entrance and exit to the album, with each song rolling on to the next one. To wit: “Crater Lake” illustrates when “you think [the relationship is] done, but it isn’t really done.” The following song, “Alice Springs,” “is saying, ‘I guess it will never work'”; the subsequent song, “May Queen,” “says, ‘Work? Who wants it?’ Like, I got over and out. It’s a real encapsulated thing. It’s almost more representational, like ‘Here are the songs that mark my journey,’ instead of ‘These are the songs I sang on my journey,’ which is more Guyville. So in a sense, it’s more removed.”

With this album thrusting her further into the public eye, Phair has been reflecting a lot on fame. “It’s been on my mind a lot, I must say,” she sighs, distractedly flipping through a pile of mail. “There’s nothing special or magic about the pop star anymore. Everybody knows how it happens, everybody knows what toll it takes. The magic isn’t in the rise, the magic is in the disintegration, like Kurt Cobain. We know how they got there, let’s see how they fuck up. This is my most harried subject, because I’m constantly changing my mind about it.”

She considers her contemporaries to be women such as Polly Harvey, the Breeders, Juliana Hatfield — women who have surpassed the conventional roles women are handed in rock. “Juliana’s a great song maker,” Phair says. “I think the personality she presents is what bugs people. I have the same problems. When all these women suddenly show up in the media, and we’re having to grapple with the whole of women’s personalities instead of the half of objectification, and we’re actually taking that whole humanity and looking at the pretty face, the weird words, the unsettling activities — people come down way too hard. They judge harshly. And so do I. But I totally respect her.”

The phone rings yet again. It’s a magazine, and Phair fires off a quick phone interview. “We should get out of here,” she says, eyeing the phone. “I’ll drive you back.” Heading downtown, she is goaded into listing men’s fashion crimes. “Overalls on guys, man,” she groans, spotting an Oshkosh-clad schlub wolfing down a hot dog. “It would be like fucking the Pillsbury Doughboy.” We tool around another corner and spot another victim of a sartorial crime. “Colored socks,” she says, shaking her head. “It’s such a nasty mess.” We pass a man unfortunate enough to be wearing a business suit at this particular moment. “Ugh. Shiny business shoes. Hate that.” We head downtown, where she gets the eye from a slick-looking male on the street. “I loathe coiffed hair on men,” she says, rolling her eyes. She pulls up in front of her inquisitor’s hotel. “Don’t you put in there that I’m a bad driver,” she calls over her shoulder as she takes off, singing to the radio. There is a moment of tension when she hits a crossroad. Then her car disappears down the street, traveling in the right direction.