By Mark Caro

Chicago Tribune, June 22, 2013

Nash Kato was the swaggering singer-guitarist of the rising Chicago band Urge Overkill in the early ’90s when he and his bandmates would hang out at Wicker Park’s Rainbo Club, and, he recalls, a petite young woman was always hitting them up for beers “in a somewhat adorable way.”

So Kato was perplexed when he got a fact-finding call from the indie label Matador Records asking about a new artist.

“They called me in a frenzy, just like, ‘Do you know this Liz Phair?'” Kato says. “And I’m thinking, well, I know a Liz Phair. I didn’t see how they could possibly be one and the same.”

Not only were they, but Phair’s album was addressed in large part to Kato and what he represented to a Winnetka native who had a crush on him. The album also harbored many more complex thoughts and feelings about female-male dynamics. Not only that, but Phair’s “Exile in Guyville,” which took its name in part from the Urge Overkill song “Goodbye to Guyville,” would become the most talked-about album of what turned out to be a watershed summer for Chicago rock.

Yes, 20 years have passed since that summer of 1993. June 8 saw the release of Urge Overkill’s major-label debut, “Saturation,” and an even bigger commercial breakthrough arrived July 27 in the Smashing Pumpkins’ major-label debut, “Siamese Dream.” The Pumpkins, like Urge and fellow local bands Material Issue, Eleventh Dream Day and the Jesus Lizard, had been building a sizable indie following in and beyond Chicago, so their ascensions felt like natural progressions.

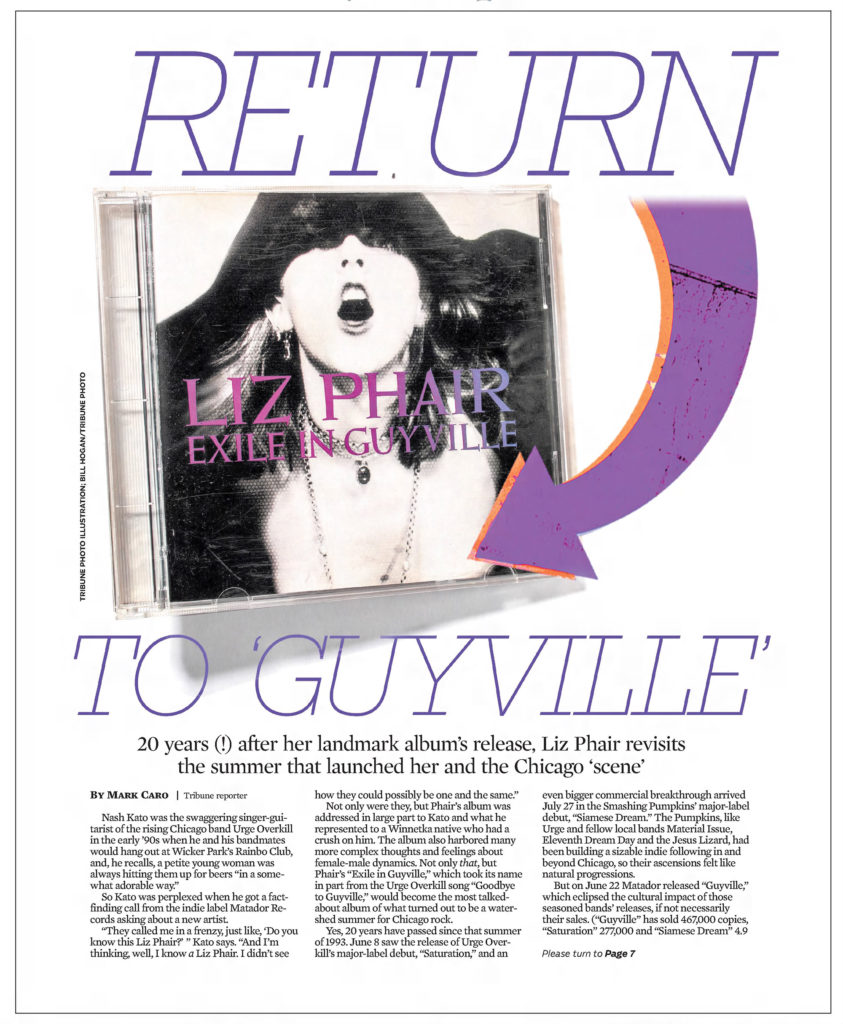

But on June 22 Matador released “Guyville,” which eclipsed the cultural impact of those seasoned bands’ releases, if not necessarily their sales. (“Guyville” has sold 467,000 copies, “Saturation” 277,000 and “Siamese Dream” 4.9 million, according to Nielsen SoundScan.)

Exploring a young female perspective on sexuality and identity with a frankness, sharpness, explicitness, anger and humor rarely heard on record up to that time — with the 26-year-old singer’s unschooled vocals spilling hard truths in a deadpan or occasionally manipulated voice over spare arrangements built around her unconventional guitar parts — the album became a rallying cry for listeners grateful that someone was expressing what it was like to be a woman in a kind of Guyville.

The album topped the Village Voice’s annual national critics’ Pazz & Jop poll as the year’s best album, beating out Nirvana’s “In Utero” and P.J. Harvey‘s “Rid of Me” (“Siamese Dream” landed at No. 11, “Saturation” at No. 16), and it was Spin magazine’s album of the year as well. Then-Village Voice critic Ann Powers wrote that “Guyville” spoke “the truth for women trying to figure it out these days.”

Phair’s follow-up albums “Whip-Smart” (1994) and “whitechocolatespaceegg” (1998) contained insightful, tuneful rock/pop but couldn’t match the debut’s zeitgeist-seizing power. And when she has tried on new stylistic hats, such as working with the slick, youth-chasing Matrix production team on “Liz Phair” (2003) or rapping goofily on “Funstyle” (2010), she has gotten slammed in language that implies betrayal, something like, “The raw, honest artist of ‘Exile in Guyville’ is giving us this?“

Such are the perils of making music over which fans feel deep, deep ownership.

Yet the shadows cast by “Guyville” extend beyond Phair’s career. It’s no longer a novelty for female singers to address sexual issues candidly, and a line could be drawn from “Guyville” to Lena Dunham‘s HBO series “Girls,” with its unflinching views on young female sexuality and its devil-may-care attitude about making the characters likable. Dunham, like Phair, attended Oberlin College in Ohio.

Phair, now 46, doesn’t revisit “Guyville” as if taking a victory lap. “I didn’t feel like that period was a happy one for me,” she says from her Los Angeles-area home, “and I sort of spent my life learning to be a better-balanced, less angry individual.”

Yet she, Kato and “Guyville” producer Brad Wood returned to “Guyville” in separate conversations to piece together how this young visual artist managed to make an album for the ages.

Back Story

Phair had home-recorded a much-copied and praised series of cassettes called “Girly Sound” that came to the attention of Matador co-owner Gerard Cosloy around the time she called him to try to get on his label. She’d also, in a non-girlfriendy way, moved into the Ukrainian Village apartment of John Henderson, who owned the local label Feel Good All Over Records and played the cassettes for Wood, co-owner of the nearby Idful Studios.

A wowed Wood signed on to record her, but Henderson and Phair butted heads at early sessions, so Henderson departed. Meanwhile, Phair decided to configure her album — which would feature some reworked “Girly Sound” songs, some newer songs and some yet-to-be-written songs — as a track-by-track response to the Rolling Stones’ landmark 1972 double album “Exile on Main Street,” which she’d recently come across.

Phair: I was very academic in my approach to it. I’m like, I’m going to make little symbols to describe certain types of songs or certain types of feels, and then I’m going to put these symbols next to all the “Exile on Main Street” songs, and then I’m going to put these symbols next to my songs … and I would try to match them up. I was also stoned, but it made sense to me.

Wood: I thought she was pushing it a little bit to find a correlation between some songs, but it didn’t really matter. The pacing of the album is pretty great, I think, and it was a great template to have.

Kato connection

Phair: He was my muse. He was the guy I was sort of singing at. Even though I didn’t write all the songs about him, once I compiled it, he was my Mick Jagger character. He represented the person that I wanted to understand, couldn’t understand, looked at a lot but couldn’t quite bring myself to go for.

Kato: She was leaving little love notes that sort of hearkened back to junior-high days when girls would shove perfumed pieces of paper through the vent of your locker (laughs).

Phair: I don’t think we ever actually went all the way (laughs). I think I was too scared. In fact I know I was (still laughing). But we had like a few entanglements, and I definitely was just gaga for him. I thought all the rest of the men in the area looked like boys in comparison.

Kato: Uh, let’s just say she didn’t attempt to conceal her enthusiasm.

Playing, songwriting

Wood: Her guitar playing is amazing. I’d like to just sit there and watch her play. She has a really interesting style, and she’s a lot more technical than either she’ll let on, because she does it in such an offhanded way, or than many other people give her credit for.

Phair: I make up my own chords if I can, and I think of the fret board as a visual thing, like if I’ve been down low and I need to do something different toward the headstock, I’ll just be like, “What can I do up high?”

Wood: Her chord structure was great, and her sense of melody is just bananas. The way her vocal melodies will just leap, go an octave and a third and back down again, I’d just never heard anybody sing like that before.

Phair: (Songwriting) was where I put my rebelliousness or my sass or what I felt was oppressive or what I felt was hurtful that I couldn’t say in real life. I guess it’s like the way you’d use a diary in a way, but it was different. It was much more like I could be a persona in my music.

Breakthrough

Wood: “(Expletive) and Run” (from “Guyville”) was the first time that she and I attempted to record just the two of us. She played the guitar once, one take. I said, “I think maybe I’ll play drums on this. What do you think?” And she wasn’t sure about that, so I set the drums up really fast in the lounge, and I used one mic and had her push “record,” and I played the drum beat, and I walked in afterward, and she was all sweaty because she’d been dancing around. She’s like, “I love it, I love it, I love it.” And I said, “Oh, great, let me do it again.”

I then went and played the drum beat again but also hearing the original drum track in my head, and I really liked the way the two of them sounded. I came back in. She’s like, “It’s even better!” I added sleigh bells, and the second time I played drums I sang background (vocals), like I just looked up at the ceiling where the microphone was and sang as loud as I could. Then she sang the vocal that night out in the vocal booth, and that song was done.

There’s just one guitar. There’s no bass. There’s no background vocals other than my singing into the drum mic. And there’s two tracks of drums. It’s the weirdest damn thing ever. That was the breakthrough as far as I was concerned.

Keeping it quiet

Kato: It was shocking to me that she had all this music in her that she was keeping under wraps. Modesty is always a virtue, but it was a bit ridiculous. We being in bands, you’d think it might’ve come up, you know, “I’ve got some songs too,” that sort of thing.

Phair: I’m not that kind of person. If you meet me and talk to me, you just wouldn’t really know what I was up to. The only reason they knew about my art is because I was trying to get people to buy my drawings.

Cover

For her cover art, Phair had turned in a picture of a Barbie doll orgy. A concerned Matador called Kato, who had art-directed the Urge covers, for help. The result was the striking photo of Phair in midroar, a fake fur coat draping her head and necklaces hanging over her bare top with just a hint of nipple showing.

Kato: One night at the Rainbo, I said, “OK, your new label, they called me and they hate the artwork. … We don’t have much time. I’m thinking you’re a girl, and sex seems to sell. Can you give it up a little?” Rainbo Room had a very famous photo booth, so I shoved her in there and gave her a stack of quarters.

Phair: The first shots are kind of normal, and then I kind of let loose. There’s that side of me. I guess you could say one of the things that “Guyville” benefits from is the tension that exists in me between a good girl and then this sort of unleashed animal side.

Later publicity shoots

Phair: The photo shoots were just always about sex, as if (the explicit) “Flower” were the only song on the record. … Everyone would be like, “Wear just suspenders over your nipples and stand on Michigan Avenue while we take your picture.”

It was so violating. Sometimes in their studios, they’d throw a party while I was taking the pictures. “We’re doing a Liz Phair shoot. Do you want to stop by and have a cocktail?”

So there’d be this group of people milling around, and I’d be wearing next to no clothes being photographed.

I mean, I get what I deserve, don’t I? (laughs) But (the album cover) was under my control.

Release

Wood: I’ll be honest: I expected the critical appeal. Did I think it was going to be as widespread as it was? I didn’t expect that. But I wasn’t surprised.

Phair: It was thrilling what was happening, but it was also traumatizing because of what came with that.

Wood: The onslaught of attention was hard to get used to at first for Liz.

Phair: You have to understand I had never performed live. Like nev-er. Not ever. I would have rather died. So all of a sudden, I have this record taking off, and everyone wants me to perform, and I’ve literally never been on a stage and played my songs.

Wood: In the audience, people would scream the words back at us so loud that I couldn’t hear anything I was playing, she couldn’t hear herself, and she would turn around and look at me like, “Oh, my God. What the (expletive)?”

Reception

Phair: They thought it was just confessional. They thought that there was no sort of self-editing process. My favorite thing is to be really brilliant while like just off the cuff. That’s my aesthetic, high-low. The fact that they didn’t think that I could be intelligent enough or artistically formal enough to intend things to be the way they were deflated me a little bit.

Also, the neighborhood that I was in really split down the middle. Half of them really resented that I’d gotten all this success when they had really been more in the scene preparing, playing, wanting it, and it felt to them like, “Oh, ’cause she’s cute and she came from the suburbs, she’s more marketable, so that’s why this is getting all the attention,” you know? It’s never fun to have people talking about you like that.

Fans

Phair: (Fans’ sense of ownership) means that there’s always a comeback available to me. They’re always like, “All right, are you going to do something good?” (laughs) I’m lucky beyond words that that’s how they felt about it. … There’s something much more lifelong about it, which suits me. Most of my friendships are very old or are on their way to becoming very old, and we’re not always friends all the time. (But) when they’re (ticked), it’s not fun.

Past and present

Phair exorcised many of her “Guyville” demons when Dave Matthews’ ATO Records rereleased the album in 2008 along with her own DVD documentary about its making. Now she is collaborating on a new album with singer-songwriter Ryan Adams producing.

“He helped a lot in giving me confidence again,” she says. “He opened me up again because he’s an artist, so he understood.”

Meanwhile, “Exile in Guyville” landed at No. 37 on Spin’s “125 Best Albums of the Past 25 Years” list last year and No. 327 on the 2012 edition of Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of All Time” list.

To Ann Powers, now a critic for NPR Music, “Exile in Guyville” has left a huge sonic legacy. “That feeling of an artist letting you in on her process and creating a sound that’s very intimate and individual, all of that comes out of ‘Exile in Guyville’ in some way or other,” Powers says.

What Powers wishes she would hear more from current artists is “the way she dealt with sexuality and relationships in a very frank but not pandering way.”

At the time of “Exile,” Phair says, much of her ire was directed at snobs who’d blather on like professors and make others feel “nonmusical.”

“I was so sick to death of them,” she says. “I just had this fire in me, like music is innate. Music belongs to the human species. I’m like, no, I’m going to do this record, I’m going to show everybody that a girl who isn’t an expert in music can still be very musical, excellently so. And that’s what I did. I believe that still.”

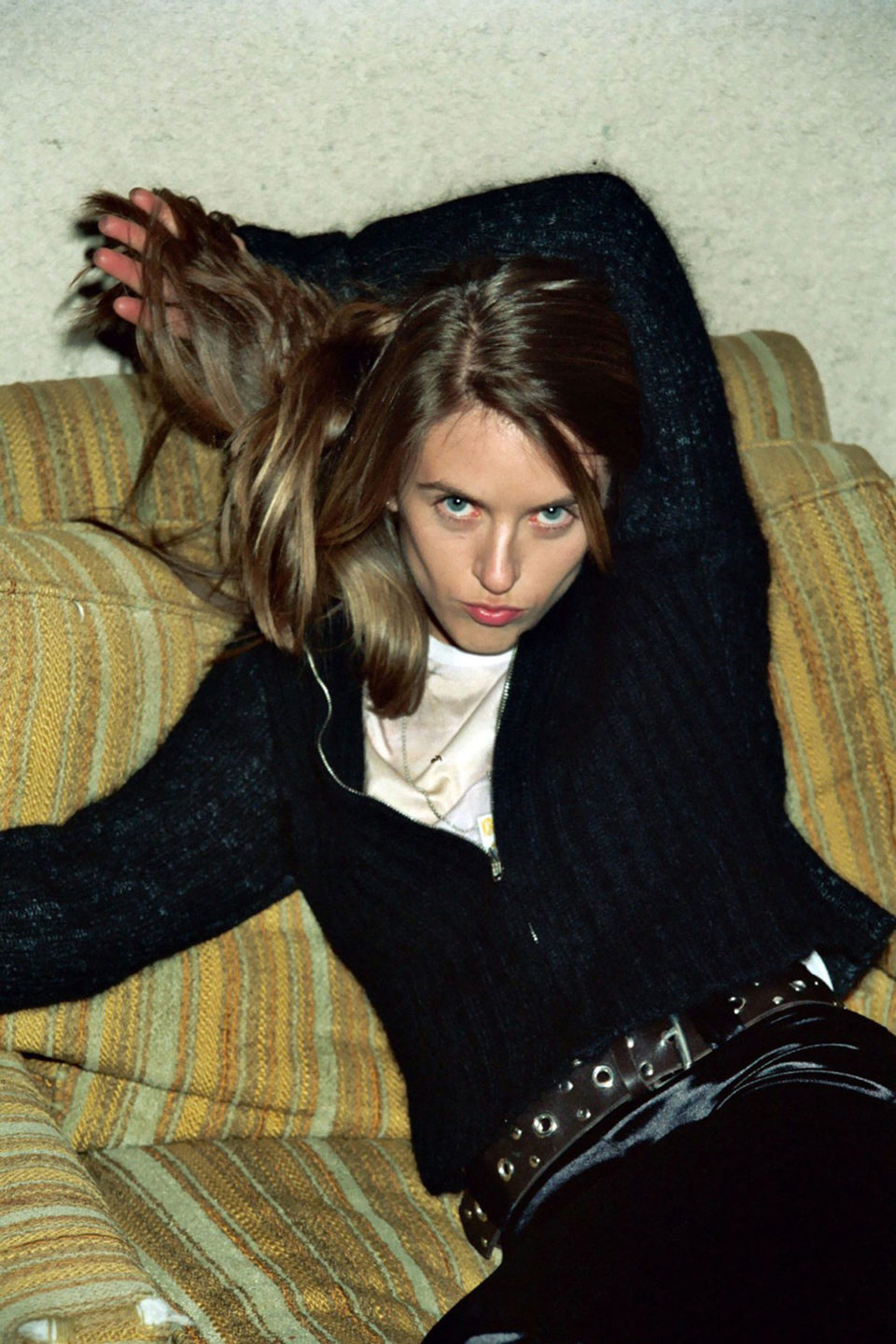

Featured Image: Liz Phair had never performed in public with a band until a few months after this show at West Hollywood’s Troubador Club in December 1993. She called the quick fame “traumatizing.” (Tribune Newspapers Photo)