By Greg Kot

Chicago Tribune Magazine, September 25, 1994

To hear some people tell it, Liz Phair is a marketing agent’s dream, the new queen of-perhaps you’ve heard of it?-Generation X. In places where matters of pop culture are measured in multimillion-dollar increments, Phair is the golden girl: an attractive, college-educated 27-year-old who fled the wealthiest of suburbs for bohemia and rock ‘n’ roll, a former starving artist-turned media celebrity. As far as the power lunchers in the glass towers of Manhattan and on Sunset Boulevard are concerned, she stands at the cusp of what matters to many young people in the precious 18-to-29 demographic.

Up until recently, she lived in Wicker Park, epicenter of a newly revived Chicago rock scene. It’s a tough, integrated, graffiti-scarred neighborhood on the Near Northwest Side with relatively cheap rents and lots of places for people in bands to drink, grouse, gossip and occasionally perform. Phair wrote an album about what it meant to live there, a woman trapped in a man’s, man’s, man’s world facetiously dubbed “Guyville.” The album — titled Exile in Guyville — was full of catchy pop songs just daring enough to seem cutting-edge, while describing explicitly, yet almost offhandedly, a woman’s needs, dreams, desires and fantasies. Lots of female rockers are being similarly candid these days, but none has captured the public imagination the way Phair has, and Phair knows why. Photogenic, literate, witty and just self-deprecating enough to make her ample ambition seem, well, charming, Phair not only makes the music, she knows how to sell it.

“My music is good, people like to sing to my lyrics,” she says, as usual addressing the subject she knows best-herself-with disarming bluntness.

“They like the way that what I say makes them feel. It’s humorful enough that people who feel uncomfortable with the more explicit stuff can let it in, and it’s kind of rocking enough for people who don’t listen to lyrics at all. I can speak articulately, and I’m cute enough that you can photograph me, and you can dress me up and I’ll do it, I’ll smile and I’ll dance around.” “Of course, I’m gonna bust my ass marketing anything I do,” she adds. “It all comes in a whole big package. There are musical lifers who don’t see it that way, to whom it’s a sacred art form. But I’ve always been a slut in that sense. I will bounce from one art to the other. This is also a business, and business is creative too.”

No wonder she has hob-nobbed on the David Letterman show, was courted and coveted by every major record company before landing a big-bucks, long-term record deal a few months ago in one of those Manhattan high-rises, has become cover material for Rolling Stone magazine and numerous other pop-culture publications, and was recently named by Newsweek as one of the 25 must-hear voices of her generation. Now she approaches another, even more lucrative level of stardom with the release last Tuesday of her second album, Whip-Smart, in many ways a more radio-friendly record than its predecessor and certain to benefit from a big-budget promotional push by her allied Matador and Atlantic record labels.

Only two years ago, Phair was begging her parents’ acquaintances to buy her “juvenile” charcoal etchings and was scamming peanut-butter sandwiches from her friends’ apartments because she was broke and hungry. She was virtually unknown outside of Wicker Park, her music still a private affair. But when advance tapes of Exile in Guyville began snaking down the local rock grapevine, the buzz brought a big crowd to Lounge Ax on Lincoln Avenue one Saturday in January 1993. At the bar next door that night, Phair was sipping tea at a table in back. Stuffed into an oversized coat, a red scarf around her neck, she looked even more waifish than her 5-foot-2-inch frame would suggest. At one point she shivered and leaned forward, gripping her stomach. “It’s nerves,” Phair explained. “I hate going up there.” “Up there” is the modest stage at Lounge Ax. A half-hour later, she was singing and playing guitar before an audience of paying customers for maybe the sixth time in her life, and it would be an ordeal. She refused to make eye contact with anyone or anything except the “exit” sign, and her amplifier kept breaking down in the middle of songs. Then a string snapped, and Phair looked at her damaged guitar the same way a child might size up a three-legged dog. Finally, she glanced pleadingly at the sound board, and the technician behind it snaked through the crowd to perform equipment surgery. Phair soldiered on, and after 25 minutes, the set-much to everyone’s relief-ended.

Yet for all the awkwardness, there was also affirmation. Enough of Phair’s music had gotten through to demonstrate an extraordinary talent for turning ambivalence into a melody, for crafting lyrics startling in their frankness. By turns scathing, poignant and disarming, Phair’s songs were as jarring as her stage presence was timid. “I take full advantage of every man I meet,” she sang with deadpan languor on “Girls! Girls! Girls!”. “Flower” described what she’d like to do to her lover in pornographic detail, while “Fuck and Run” body-slammed the rogue for his lack of commitment. Pretty soon she was dancing on his grave: “And I kept standing 6-foot-1 instead of 5-foot-2, and I loved my life, and I hated you.” But the evening’s most prescient tune was “Help Me Mary”. In it, Phair railed against the “Guyville” scene that both spawned and repulsed her: They treat me like a pit bull in a basement And for that, I’m asking you Mary Please, temper my hatred with peace Weave my disgust into fame And watch how fast they run to the flame. Sometimes people get what they wish for, and regret it. Phair, however, hasn’t looked back since.

The songs that night at Lounge Ax were even more riveting as heard on Exile in Guyville, released a few months later on the New York-based independent label Matador. At year’s end, it was acclaimed the album of the year by many music writers, swept the nationwide critics poll in the Village Voice, and helped turn Wicker Park into “the capital of rock’s cutting edge,” as proclaimed by the record industry bible, Billboard magazine. “Guyville is, in its emotional palette, almost the Pet Sounds of girl rock,” wrote Sue Cummings of LA Weekly, comparing it to the Beach Boys’ highly personal, multifaceted ’60s masterpiece. That the album articulated the feelings of a significant, if long-ignored, segment of the population also was not lost on Village Voice critic Ann Powers, who said it spoke “the truth for women trying to figure it out these days.” Guyville continues to sell and has pushed past 200,000 copies — remarkable for an album released on an independent label with an initial promotional budget of $700 and virtually no mainstream commercial radio airplay. And it turned Phair into “Savoir Phair, she’s everywhere,” as one local fanzine writer quipped. Even before the record cracked the Billboard Top 200 last January, Phair was dishing out saucy quotes and flaunting her perky figure in magazines and newspapers and on MTV.

With the attention and the celebrity has come a backlash, a speciality of the notoriously suspicious local music community. Brad Wood, Phair’s friend, drummer and recording engineer, only half-jokingly calls her “the most hated woman in Chicago.” “A rich suburban girl who made a name for herself (by) having an incredibly aggressive publicity campaign come to bear on her,” declared underground tastemaker and noted recording engineer Steve Albini. Phair once used to take such criticism hard; she cried when she got her first bad review, and she wrote a letter to Spin magazine contesting another. Now she laughs it off. “Damn straight I’m manipulating my career and the media,” she says, while serving a visiting member of the media a bowl of homemade pasta. “I don’t mind treading the fine line between doing something interesting and valuable for society and totally just exploiting my popularity. I’m 27, I’m ready to cut my teeth on something. If it wasn’t this, I’d be blasting into offices somewhere else wanting to get to the top of the corporation. It’s ambition. Total, simple ambition.” Puttering around in running shorts in the kitchen of her Northwest Side couch-house apartment, Phair doesn’t look particularly ambitious. She seems slightly out of place, but, hey, the pasta salad isn’t bad.

Chrissie Hynde, Phair’s predecessor as the pre-eminent female rocker-celebrity of her time, says, “I’d need Valium, I’d be in tears if I had to plan a dinner party.” Phair looks like she’d find a way. She always does. “I have a really good ability to get where I want to be, to find whatever it is and keep traveling until I get there,” she says. “Some years it takes longer, but it always happens.” “She can’t even imagine the possibility of failure,” says John Henderson, who three years ago first brought Phair into a studio to record her music. “I love Liz, but she seems to get her way every time,” says Chris Lombardi, the copresident of her New York-based Matador label. “She can be frustrating. Oh, God, yeah… I’ve had my head in my hands many times around her.” After one run-in with Phair last summer, somebody in Matador’s Manhattan office carved a swastika into a poster of the singer. Phair laughed when she saw the backhanded tribute to her stubborness. “Face to face, we get along fine,” she says of her record label. “Behind each other’s backs, we bitch about each other. I have no problem with that.” One of the reasons Phair has been complaining lately about the business of making music is that it takes her away from her live-in boyfriend, Jim Staskauskas, and his 15-year-old son, Aidan. The teenage punk rocker in her life is off at the Lollapalooza rock festival on this day, listening to bands like Smashing Pumpkins and the Beastie Boys. Staskauskas, 36, is at his job as a film editor at Optimist studios, and Phair is fantasizing. “Wouldn’t it be nice,” she muses, “if Jim and I were to get married, and I’d get pregnant? And then I could spend the rest of the year making music and videos in my apartment without having to tour. Is that any way to sell a half-million records?” she asks a visitor. Phair laughs. “I have this real dark feeling that this year I’m going to do what I’m not supposed to. I’ve been talking about not doing what I’m supposed to for a long time.”

Elizabeth Clark Phair was adopted as an infant in New Haven, Conn. The family, including older brother Philip, then moved to Cincinnati and finally Winnetka. Her father, John Phair, is now an AIDS researcher and head of infectious diseases at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Her mother, Nancy, teaches at the Art Institute. Phair went to New Trier High School, surrounded by money, ambition and “a high percentage of people with access to expensive grooming products.” She wasn’t the girl most likely to rock back then. “There wasn’t rock ‘n’ roll at New Trier,” she says. “There were 4,000 ‘Buffy’ people, and three punk rock kids, and we’d stare at them in the bathroom. Nobody looked like that.” Phair excelled in academics early on, with ambitions of becoming an artist, but soon discovered there was more to life than good grades and expensive clothes. “I was in the back seat drunk, and so was my friend who was driving,” she says, recounting one high school joy ride straight out of Risky Business. “I remember seeing this telephone pole coming at me as I was leaning out the window and my hair was flying and I felt it brush against the pole as we whizzed past it. That encapsulated my need for thrill-seeking. “I like to drive fast, but I don’t like to be the one driving. I like to be in the back seat saying I shouldn’t be here. Her grades fell but she showed enough promise that she was accepted at Oberlin College, a prestigious liberal-arts oasis in Ohio, where she spent four years studying art history. “I was very sheltered and always felt very safe and taken care of. I realized that I could be unpredictable, chaotic, and let a night happen, and it would take meaning in the chain of events. There was a whole social element to it. A whole new way of having fun. Now I was bad — still a virgin, but I was bad. It was the world of the imagination, and boy, did I have an imagination. The first inklings of freedom of choice, everybody goes through that. I just happened to take it up with a fervor.” During breaks from college, Phair and her old New Trier pals would congregate at the Heartland Cafe in Evanston to chatter, flirt and dream. Phair would drink whiskey on the rocks, smoke cigarettes and act like she belonged, even though she wasn’t even 21. The goal was to “bag the hottest guy who walked in.” Did you find him? A smile, somwhere between embarrassed and bemused, alights. “He doesn’t exist. Every evening, there’d be two hours of fabulousness and then … crash.”

Phair drifted after Oberlin, whiling away a year in San Francisco trying to make a go of it as an artist before coming home broke to live with her parents. To indulge her “poetic, drippy side,” she began writing lyrics, playing guitar and singing songs into a four-track tape recorder in her bedroom. Eventually she filled up three cassettes with music, dubbing them Girly Sound, for the amusement of a few friends. John Henderson, who runs the respected Feel Good All Over record label in Chicago, heard the tapes and was intrigued. Soon Phair moved into his Ukrainian Village apartment, an easy walk from Brad Wood’s Idful recording studio. The idea was that she would re-record the best of the Girly Sound songs there and make a more finished album for commercial release. “It was an opportunity and a fluke, and I went with it,” Phair says. “The music was the same thing as art, only I got recognition. So I thought, ‘Cool! I’ll do this for a while.'” “Typically, she’d write a song and play it for me and it would be there, entirely,” Henderson says. “She had such a weird way of playing guitar, because she was trying to incorporate everything that one would hear in a fully produced record. It was percussive and melodic at the same time.” But when Henderson and Phair tried to re-create that feel in the studio with Wood, they floundered. Henderson and Phair soon began quarreling about what direction to take: He wanted a stripped-down but precise sound, possibly with outside musicians; she wanted to rock, on her own idiosyncratic terms. “We both wanted something for me,” Phair says. “He was projecting onto me what he wanted my music to come out like, which was wrong. So I blew him off.” Henderson was the first member of the music community to find out how tough and stubborn Phair could be. He became so disgusted by what he saw as the musical compromises she was making that he stopped showing up at the studio; Phair moved out of his apartment and began working with Wood exclusively on the music that would become Exile in Guyville. “I’m reminded of the famous Greil Marcus quote about Rod Stewart, something about how he wanted to be a rock star and all that entailed-sitting by the pool, having sex with groupies and snorting coke-and if he had to write great songs to do it, he was perfectly willing to write them,” Henderson says.

“I think she betrayed her talent in much the same way.” Henderson nonetheless tipped off Wood that Matador was interested in Phair’s music based on the Girly Sound tapes. “The relationship between Liz and me had become so strained that I realized it wouldn’t last long enough for the album to be any good,” Henderson says. “So I figured why not let somebody else do it.” Wood called Matador copresident Gerard Cosloy the next day. But the split was less than amicable: Henderson hasn’t had any artists record at Idful since, even though he has made a number of albums in Chicago.

Despite his significant early role in its creation, Henderson didn’t receive any credit on Guyville but says the album isn’t anything he’d want his name on anyway. “I have very little ill will toward Liz,” he says, “unless you consider aesthetics.” In listening to the Girly Sound tapes, which pile on irony, wit, bile and sophomoric poetry in equal measure, it becomes immediately apparent why there would be disagreements over how to make a commercial pop record out of these songs while trying to retain their initial charm. Sometimes, a pallid compromise was all that was achieved: In its gussied-up form on Whip-Smart, a song such as “Shane” loses the disarming intimacy, the almost spooky interplay between Phair’s voice and guitar achieved on Girly Sound. But in general, Wood deserves credit for helping Phair make the shift from bedroom folkie to rock headliner.

Most albums are built from the ground up, with the rhythm section recorded first and then the guitars and vocals layered on top. Wood worked backward, with the help of guitarist and engineer Casey Rice, structuring the drum patterns and bass lines around Phair’s vocal phrases and guitar riffs. The procedure was much the same on the new Whip-Smart, one of the year’s most highly anticipated rock releases. Unlike the debut, it will get a major promotional push from Atlantic Records, which is now in a sugar-daddy partnership with Matador. The five-album deal with Matador/Atlantic “is huge,” says Matador copresident Lombardi. “It’s as big as any indie signing has ever been. Every major record label in the U.S. was willing to sign her, and we had to match the value.” The deal is reported to be in the mid-six figures. Atlantic president Danny Goldberg, who won the bidding for Phair, figures she’s worth it. Not only did he give her a generous deal, he offered her total creative freedom to record what and with whom she likes and also to direct and script her own videos. “Our relationship is she sends us stuff and we say, ‘That’s fabulous.'” Goldberg says he was impressed by Phair from the start even though “our first meeting was not very good.”

“Everything I said was wrong, and she was using swear words: She didn’t want to do shows, she only wanted to do records and videos. Whatever I said, she argued about.” But he persisted. “There’s a quality she has, a weird kind of anti-charisma. She wears very little makeup, if any at all, and is very down to earth, yet has this odd magnetic quality. In concerts, she doesn’t do anything dramatic. Someone wrote a review in which he said the audiences are rooting for her to hit every note. She doesn’t go out and grab people so much as draw them in. She’s a one-of-a-kind thing, a star.”

To others, her eagerness to sell, sell, sell, undercuts her songs. One of the few label executives who did not request anonymity when questioned about Phair was Bettina Richards, 29, who operates the Chicago-based Thrill Jockey Records. “The only thing that’s aggravating is that there are other female songwriters I love that I couldn’t understand why they’re not getting the attention Liz Phair is,” Richards says. “Barbara Manning for one. To me, her lyrics are so sophisticated, but she’s also not aggressive about wanting to be successful. I don’t see her ever putting her chest on a record cover.”

Phair did just that on Exile, and the album drew a few leers because of several graphic sexual references in the lyrics, particularly in the song “Flower,” and an inner sleeve decorated with soft-porn photos of a woman resembling Phair. Phair also described the album to journalists as a response to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street, seemingly oblivious to the heresy she was committing by daring to mention her debut in the same breath as the holy grail of ’70s rock criticism. As profiles of Phair began to proliferate, her scattered explicit lyrics, Madonna-esque boy-toy photos and more outrageous pronouncements began to overshadow the album’s depth and richness. “It’s embarrassing for me that those songs, those lyrics, would’ve been taken out of context,” she says. “They lose their humor and intelligence. I thought it was pretty savvy to do ‘Flower’ in a little girl voice. To me that was a statement in itself about what you can do about pornography, how to throw it back in the face of society. The point of some of those songs was to say things that shouldn’t come out of the voice that was saying it.”

“The songs are total fiction. The feelings in them are true, but the stories are lies.” Those who actually listened to the entire album, who enjoyed the irony for what it was, found a variety of perspectives about the toxic consequences of intimacy. They found a songwriter who could be confessional and vulnerable, but also tart and humorous, one who could break into an Ethel Merman voice to sing lines such as “I get away, almost everyday, with what the girls call murder.” And, whether the lyrical sophistication was appreciated or not, Guyville rocked — a punk-folk album that cut through the flannel-and-grunge decade like a shark fin. It was audaciously accomplished music for an artist who virtually never played live before. This aroused suspicion and jealousy in the real-life “Guyville,” where playing low-paying Wednesday night gigs is the way to build credibility. “My critics saw me as the lucky daughter that new daddies are going to take and make,” Phair says. “And (they ask) why do I deserve it? But it’s not about deserving it. It’s about the path of least resistance.”

“I’m accessible enough in so many channels, and you can sell me really well. You don’t get big money based on merit… it’s not an issue in this equation.” The path of least resistance can also mean cutting corners when it suits her; feelings have been hurt and gossip spread in retaliation. The term “Guyville” originated not with Phair but with a quick-witted Hyde Park musician, Chris Holmes, who was struck by Wicker Park’s “twisted cosmology of what it means to be a guy: tapping your foot to music that’s not there, checking out a girl while pretending to look at your beer bottle… It’s almost something to be ashamed of.”

The term was adopted by local band Urge Overkill in the title of one of their songs, and Phair — who is friendly with both Holmes and the members of Urge — found it a fitting umbrella for her album. In interviews, Phair mentions both Urge Overkill and Holmes, but both go uncredited on the album. It’s notable only because the word “Guyville” has become part of the pop-culture zeitgeist; at least one Hollywood script is being floated using the word in its title.

A more serious careerist criticism is leveled by Henderson, who bashes Phair for “talking about how male-dominated the record business is in her interviews” and then hiring established figures such as Will Botwin to be her manager and Bob Lawton as her booking agent. One female who Phair did solicit to help her was Katy Maguire, who directed Phair’s first video, “Never Said Nothing.” Her payment was exactly that: nothing. But Maguire says she doesn’t feel cheated. “We did a video that would’ve cost at least $30,000 for $7,000, mainly because her record company wouldn’t allow her to do one any more expensive,” says Maguire, a two-time award winner at the Illinois Film Festival. “But she did me a favor too. The fact that I did that video is the first thing people notice on my resume.” Maguire says she’d work with Phair again, if she got paid. “She does what she has to do to get ahead,” Maguire says, “and in a way I’m the same way.” On her new Whip-Smart album, Phair does come out ahead, if only after a long struggle. She opens this song cycle about a woman’s self-discovery with a hushed piano nocturne, “Chopsticks”. It recounts a meeting at a party, a graphic promise of wild sex and then… nothing: “I dropped him off and drove him home, ’cause secretly I’m timid.” By album’s end, however, Phair is giving the guy she once craved the bum’s rush.

“Don’t be fooled by him,” she warns, and then turning to the object of her disaffection, she offers a blithe kiss-off: “You were miles above me/Girls in your arms/You could’ve planted a farm/All of them hayseeds.” Whereas at the end of Guyville she’s still sorting out her emotions, at the climax of Whip-Smart she blows town, scattering her former lover’s empty promises like so many wild oats. As the album progresses from lust to recognition to rage and finally to independence, the songs have women and men swapping roles in a fairy tale world filled with lions and tigers and bears. In this magical realm, almost anything is possible — men can even stand inside a woman’s shoes. On the album’s title track, a male Rapunzel is locked in an ivory tower, while his mother offers a prescription for escaping it. “It’s saying to the guys, ‘This is how women get out of their traps. It’s applicable to you,'” Phair says.

“The whole album is a woman’s statement, more so than Guyville, which was more introspective, more about expressing feelings that had been suppressed. I’m asserting my right to be who I am, which is the best feminist there is.” More convincingly, the album asserts Phair’s ability to write great pop songs. With “Super Nova”, “Cinco De Mayo”, “Whip-Smart”, “Jealousy” and “May Queen”, the album has a bounty of potential hits. “I’ve always been obsessed with the idea of stuff that I listen to on the radio, and I wanted to be what I’d experienced,” she says. “I want to contribute to my generation’s sounds, what it associates with the times. ‘Girl rock arises.’ I want to be prominently in that. I want to be part of what girl rock was, circa 1994.” That Phair is already speaking of her new album, indeed, her career in music, in the past tense is no slip. She talks about building a “nest egg” so that when she’s no longer “Little Miss Wonderful,” she’ll have a financial cushion to begin some other, more likely less-lucrative, artistic endeavor. “I think I’ve got it pretty good, but I don’t like the frenzy of it, I don’t like the fear and the pace,” she says. “Rock demands that you hit and get out. Or you become one of those lifers; I’ve seen their faces and they’re just withered… They have that total hardened look about them, that seen-it-all look. After the last year, I can already tune a lot of it out, I’ve become tougher-skinned, and I’m not sure that’s a desirable thing. “This profession is a little more extreme than a lot of other professions. People don’t have a lot of sympathy for that because you get all the big freebies, but really all any of us are doing is packing away the money for when we’re out on our ass and starting up the next phase of our life.”

“I’m gonna make sure that when I come out of this I don’t just land back where I was at 23.” But wouldn’t she miss the attention? Phair spikes a pasta shell with her fork and shakes her head in dissent. “But here’s what I would miss: The fact that anyone wants anything I’ll do. It would be a bitch to say: ‘I’m a great director, look at this. Look at what I can do.’ Now it’s like, ‘Great, fantastic, thank you so much.’ When I don’t have the ultimate saleable thing anymore, when Liz Phair is no longer the voice of the now, and is just the voice of nostalgia, I’m gonna have to get back down there and hustle someone else like people have been hustling me. And that’s gonna blow.”

Like a “Guyville” guy, pop culture is fickle; “the voice of the now” is constantly being rediscovered, scrutinized and discarded for another even more daring and photogenic. Like a “Whip-Smart” gal, Phair has figured out how to play the game on her own terms-with cunning, a hint of ruthlessness and a wink. She enjoys the celebrity game for what it is: frosting, froth, banter, packaging, mirth. But Phair the Celebrity has caused Phair the Artist to be perceived differently. In the months when Exile in Guyville was just a great album instead of a phenomenon, it was the songs that caused a stir. Now that the music has been reduced to a glib quote attached to a dimpled smile, it seems most opinions about Phair are based on anything but the songs. Virtually any pop performer who has tinkered with irony and image over the years — most famously David Bowie, Prince and Madonna — has been branded a fake or worse, and had their artistry demeaned, their sincerity questioned. But Phair is among the first of these pop chameleons to spring to success from the ’90s underground, and as such the ideological crossfire is especially intense.

On the one extreme is the indie-rock crowd that craves raw honesty from one of its own, and cringes when the music is undercut by the slightest hint of self-promotion. On the other is an industry that thinks of music in terms of packaging and economics, and has finally found an “indie-rock queen” to sell. Phair’s strategy is to try and have it both ways, which tends to bug both sides. In her music and marketing, contradictions collide — “Shirley Temple joins a biker gang,” as she describes it. The songs on Exile and Whip-Smart rarely embrace one emotion, their “raw honesty” seldom can be distilled into bumper-sticker platitudes. Instead, the overall mood is one of ambivalence and irresolution, each song like one view from a merry-go-round, the perspective ever-changing. Just as the songs resist instant categorization, Phair’s primping and posing in photos and interviews can’t easily be dumped into the bin marked “cheesecake”: She can be coquettish, but she’s also the girl next door, the woman of substance, the tom-boy with a guitar.

In taking her too seriously, one misses the joke, the thrill of the ride. In taking her not seriously enough, one dismisses a songwriter who weaves plainspoken confession and poetic fantasy into insinuating melodies. Phair keeps threatening to outsmart herself on the way to selling a million records, but one senses she wouldn’t have it any other way.

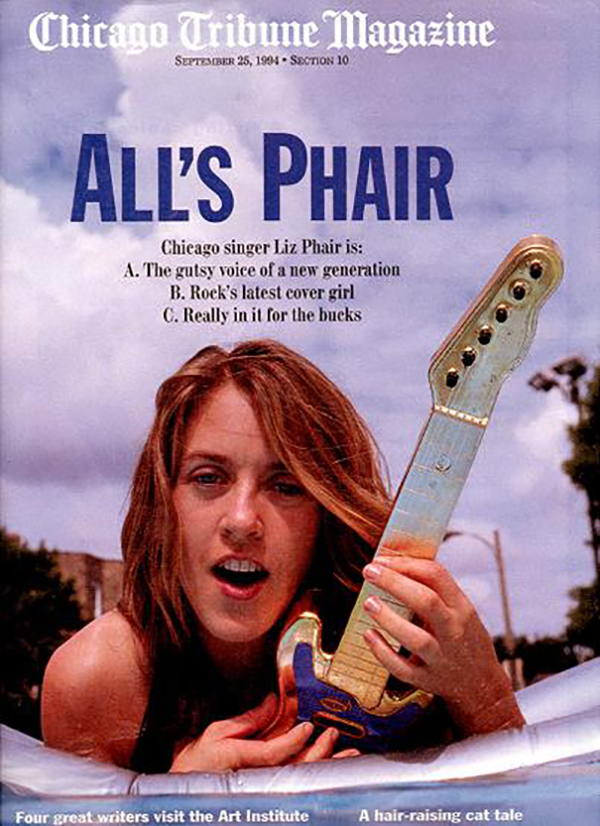

Featured image: Liz Phair poses in the public pool in Bucktown in August 1994. Photo by Nancy Stone / Chicago Tribune.