By Stephen M. Deusner

Pitchfork, June 30, 2008

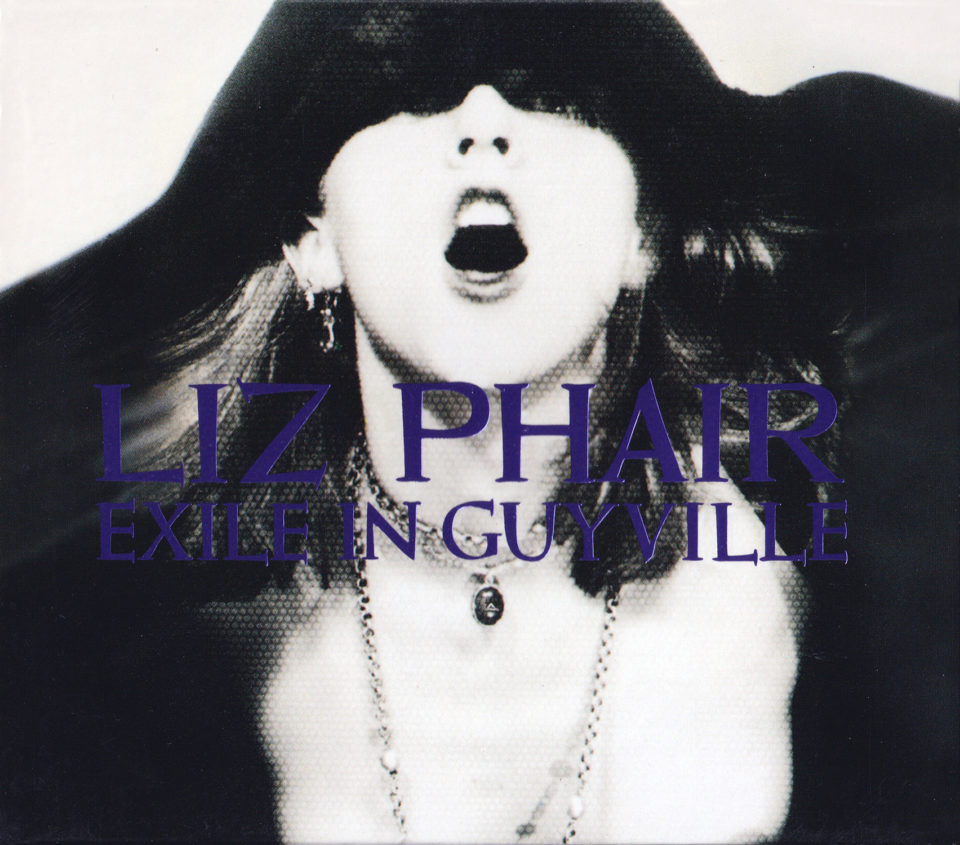

Liz Phair is spending most of 2008 living in the past. She’s composing music for the potentially controversial CBS show “Swingtown”, about sex, marriage, and key parties in the 1970s. In addition, Phair has been readying the reissue of her gutsy, glorious 1993 album Exile in Guyville, which she is playing in its entirety in acoustic shows this year, and which she unearthed four new old tracks and filmed a video documentary about the Chicago scene in the early 90s. Pretty much everyone who heard Guyville appears in the DVD and says his or her piece: musicians, label heads, producers, writers, friends, crushes, and John Cusack. Just prior to its re-release, Pitchfork spoke with the very candid singer-songwriter about signing to ATO Records, relearning old sounds, recording new material, and whether or not albums can have word-of-mouth appeal anymore.

Pitchfork: First of all, how did you hook up with ATO Records?

LP: It was a lovely little thing actually. When I was touring for the Liz Phair CD, my tour manager was Brett Radin, who’s this awesome guy. He makes touring really really fun, and for me to say that is a big deal. After working together for about a year, he told me that he was leaving. And I was like, wha? He said he was going to go be Dave Matthews’ personal assistant. And in that second, I looked into his eyes and he looked into mine, and I saw exactly what I wanted to do and where I wanted to be, and slowly got to go to shows and meet Dave and talk to him about maybe signing me. It ended up being a really wonderful thing. The only thing I could bear to lose Brett over was going on to something so awesome and great like the Dave Matthews Band.

Pitchfork: And they’re the ones who approached you about reissuing Guyville?

LP: Yes. I thought it was a great idea. I thought we were going to do it after I made the new record, but they want to do it first, so I sort of switched gears and threw myself into making the documentary. And I think it’s worked out very nicely. They’re a very smart business. It’s totally unlike anything I’m used to dealing with in terms of being on a major label. They’re like the great teacher you get in high school. It’s still high school, but for the first time you feel motivated to work and you’re interested in what you’re doing. That’s how I feel. I feel like I got a really great teacher.

Pitchfork: So this is like being back on a small indie again?

LP: Exactly. They let me do what I want as long as I don’t blow my budget. They’re like, OK, just do something good. It’s totally within my control again and it’s fun. It feels like real expression again, not trying to find expression in an already established format.

Pitchfork: What’s it like to excavate these songs again?

LP: It’s kind of a nightmare to contemplate having to figure out what I was playing on guitar in all of them. I’m not sure I’m going to get all 18 right. I know how to play most of them. It’s good in a way, because there are a lot of songs I leave off my sets that I can’t go to because I don’t know how they were made anymore. So I’m hoping it enriches my live show in the fall.

Pitchfork: Any new favorites?

LP: Yeah. The last song. [“Strange Loop”] I have no idea what I’m playing. With 18 songs, sometimes you don’t give it a full listen. That’s one of the ones that I haven’t heard as much as the other ones, and I’m appreciative of my songwriting ability back then. That’s pretty cool.

Pitchfork: You mention in the documentary that the Liz Phair of Guyville sounds like a very sad person. Do these songs still evoke the same emotions for you?

LP: They evoke a period when I was on the edge. I was not living up to the expectations of my family. What I had been raised to do I was certainly not doing. I was scamming my way through life, not really working. And I think I had some self-destructive tendencies. But it was also wild and fun. I was probably my coolest back then, and I’ve seriously fallen off the cool radar now. But at the same time I’m a lot more secure now, I think. There’s something grounded about getting older. You get older and you have to deal with yourself. Going back and listening to those songs is kind of titillating for me because listening to the person I was makes me feel a little sexier, a little cooler, a little more dangerous, a little Angelina Jolie, which I don’t mind so much right now.

Pitchfork: Guyville defined a lot of people’s 20s that way.

LP: It’s interesting, isn’t it? I’ve always heard from fans about it. I don’t think a year goes by without a healthy dose of Guyville appreciation. It seemed like I articulated what a lot of young women were feeling that hadn’t come out in the culture yet in that way. The good girl next door who can also have very a rich and shocking and progressive inner life.

Pitchfork: With such a strong connection to listeners, I’m curious how you think it will connect with these same people as well as with new twentysomethings.

LP: I have no idea what a new listener would think of it. I couldn’t even imagine. Probably like, “she can’t even sing.” After “American Idol”, they’re probably like, “I don’t get it.” I have no idea, but it can’t be that different for a fan as for me. It can’t be that dissimilar. I think there’s something great about resurrecting your past. Each listener will have associations with it if they really cared about the record– that was the summer they were dating this guy or driving cross-country with their friends or whatever. It was far enough away that I hope it has that feeling and doesn’t threaten you. Good ol’ nostalgia.

Pitchfork: It definitely seemed like when it came out, it spread so much by word of mouth that a lot of people felt they had some ownership in it. It was theirs.

LP: When everyone was pissed off at me for going with the Matrix and going pop and going for radio, I could understand why they didn’t like it, but I couldn’t understand why there was this personal vehemence. And you just said it in a way that makes me understand a little more clearly that because it was word of mouth, that’s where the ownership came from. They feel like they made me through word of mouth. I know that sounds pretty obvious, but until you just said that right then and there, I hadn’t thought of it in quite that way.

Pitchfork: And that’s what I was going to ask about. It doesn’t seem like albums can spread that way anymore.

LP: I don’t know. Don’t you think that the whole MySpace thing is that just in virtual? Isn’t that the same thing?

Pitchfork: I can see that, but it still seems so systematic. And by now it’s no longer a surprise. I thought that slow word of mouth built some mystery around it.

LP: Well, don’t you feel that way about the past in general? It was slower, and it was a little more personal. I don’t think that’s my imagination. I think it really was. Our culture speeds up, and things are less and less personal.

Pitchfork: Well, I don’t want to seem like one of those guys who says, “Back in my day it was better.” I was just thinking the differences between now and then suggest that even word of mouth today is governed by publicists and blogs– many of which are fed by publicists– and things like that.

LP: Like all those list sites that are like, this is the coolest, latest thing. You go to someone else to get the coolest, latest thing. But that’s no different than the guy who always got around town. I remember guys in Chicago, speaking of nostalgia– and I sort of talk about this in the documentary– if you had a friend you ran into at night at a club who ran in a couple of different worlds, you’d always listen to what they said was going on in the other sides of town, what was cool in this scene or that scene. I’m going to vote with the glass half full and say that our virtual network is just as gossipy and personal.

Pitchfork: You also mention in an interview that you felt creative for the first time in 15 years. Can you–

LP: [laughs] That’s so funny! I had an interview with a person who was really just stuck on that point. “How can you say that? You just negated everything you’ve done in the last 10 years! Do you want to take that back? Wouldn’t the word control be better?” And I was like, “OK, I cede to that. Control is a better word, and I’m really really sorry.”

I’m an artist who likes the process of things. I really get off on how I get from point A to point B. That’s where the thrills are for me. Just like you were saying when you were bemoaning the loss of a less structured way to find out about music– I was also sad because I didn’t feel like my creative process was happening. But ATO has given me shockingly full rein to do whatever the hell I want. That connects me once again to the artist side of myself, which is the part that I really live for. I can do the business stuff and I like that. Being on a major label, you could fight all you want, but it was a big… I love that I can say it was. It was a very generic plan: There were three channels to success, and you had to pick one. I could adapt, and I did adapt, and I tried my best to go as far as I could in those three channels, but it was never very artistic.

Pitchfork: How does the new stuff sound?

LP: It sounds a little unleashed. I have more vocals behind myself. It’s sloppy, but it sounds good. I’ve been working with dub, and I’m all about less is more at this point. I stop the minute they’re at that magic demo level and I won’t let anyone touch anything. Everything has to be open and clear, and I think once I get my nine or 10 songs I want to do, I’ll go in and layer. Some of them are very pissed off. There are a few touching ones about the vulnerability you feel as you start to open your heart to somebody. And there’s sort of a sexual one, I guess. I only have six that I know for sure for sure are going to be on there.

Pitchfork: So this is sort of backing away from the last two Capitol Records?

LP: I never think of it as backing away. I think of it as moving on. I don’t know about you, but I tend to be pretty impacted by my environment, but I usually find my own place in it. And I’m always going to be interested in pop in some form. If you listen to the Girly Sound tapes, which were long before Guyville, they’re pretty pop. It’s not like I went pop out of the blue. Now they literally give me a budget and say, “Allot this where you think it wisest.” And off you go. That’s not what it was like before, so maybe I hear more of my natural prankster self coming out.

Pitchfork: Some people I’ve talked about the reissue are disappointed that those Girly Sound songs aren’t included. Are there any plans to reissue them?

LP: That could be fun, just pass them out free, just like they were originally. I did something really funny to John Henderson [of Feel Good All Over Records, which was originally slated to release the album until a disagreement between Phair and Henderson] in the documentary, because it was his turn to say his piece, and he was like, “Well, you know, pretty much everything on Guyville was what we worked on.” I was playing “Fuck and Run” under that scene, but it’s actually Girly Sound, which sounds so much like “Fuck and Run” on Guyville that you don’t even notice it for a while. Or even ever. On the documentary, everybody has to be able to say what they want to say, but I have to be able to say what I want to say. We tend to disagree.

Pitchfork: There was a nice range of opinions on the documentary. Henderson in particular was very vocal about his dissatisfaction with the album.

LP: I think Tae [Won Yu] didn’t like it either. I also have Steve Albini on there, and you know, he didn’t take that shot. It’s kind of neat to watch because I thought it was sort of eloquently done. He kind of sidestepped and said it was an important record for women in that period. I went back and read some of the things he said at the time, and they’re very funny. I don’t mind people not liking me as long as there’s mutual respect.

Pitchfork: You’ve been pretty busy this year, between the new material, the reissue, and writing for “Swingtown”.

LP: Funny you should mention, because I’m on my way to a session right now. I’m going to Evan Frankfort’s studio over at the old Motown building, which is really cool to be in. And [Marc] “Doc” Dauer is my other partner, and we have a company now called Three-Headed Monster that was just made so we could have a company. Because my name tends to get all the attention, which is unfair because we all three work really hard on it. When we go in there, it’s a pretty fun fuckin’ thing to do. I go into the studio. It was an old screening room, so he’s got the screen up with the speakers behind it, and you can play your part while you’re looking at the scene on the screen. Or you can do it a lot of different ways. But it’s become a graveyard for all these little riffs from all my songs, either put out or unreleased.

It came about because I grew up with the show’s creator, Mike Kelley, and we went all the way from elementary through high school together, and stayed friends after that. He worked as a TV writer, and we were both on hard times a while ago, just bottoming out. I couldn’t get off Capitol and was miserable. I was supposed to leave, but [Capitol CEO and president] Andy Slater turned around at the last second and said, “No you’re not going.” And he had no plans to put out any records. He was just holding on to me because he could. It just sucked, and I was depressed. Mike was also at the end of his tether in his work situation and wanted to create something that he really cared about.

I remember when I got the script and Mike said, “You’ve got to do the music for this.” I read it, and it was so well written, but I was just ending a relationship and was in pain. And he was like, “Just trust me.” When they shot the pilot, I was just so blown away. It’s the story of a family that we both grew up with. They know about it. They’ve come to all the “Swingtown” parties. They’re in our little hometown where honestly if I took you there today, you’d be like, “God this place is so conservative and prudish. How could “Swingtown” have happened?” But the gossip is just going like wildfire. My mom told me at the dinner parties she goes to now they’re like, “Did you know about the little struggle that was going on at the Winnetka Yacht Club? And I heard about the downtown theater group?” Everybody’s coming clean about the 70s and what they were really doing.