By Joshua Alston

Newsweek, June 30, 2008

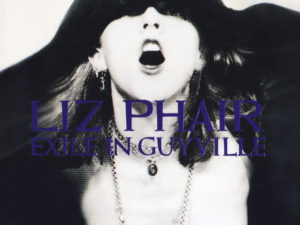

A reporter recently asked Liz Phair what it was like to be hated by everyone. “He said it just like that, totally matter of-fact,” says Phair, still in disbelief. “Obviously it was a huge pain in the ass.” Nor is it fun to answer endless iterations of such a prickly inquiry. But by now, Phair, 41, knows that question is coming. This week she’ll rerelease her debut album, Exile in Guyville, to commemorate its 15th anniversary, in a deluxe edition that features previously unheard tracks and a documentary she directed. It’s a celebration of the album that got her beatified by the rock cognoscenti — and also set her up for a reversal of fortune when her most ardent fans revolted against her. The story of Phair’s fraught relationship with her finest work isn’t about what it’s like to be hated. It’s about what it’s like to be loved, then hated.

Guyville was released in 1993, when a wave of bold female voices in rock was cresting. Phair was unique among them, because while she wasn’t afraid to rail against the rock patriarchy — the album was conceived as a song-for-song response to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street — she also wasn’t afraid to display her sexuality in an unflinching way. It was an honest, funny, complex portrait of a young woman defining herself. No wonder, then, that it resonated deeply with tastemakers and critics. While it never put up boffo sales numbers, its cultural impact was huge, bringing Phair the kind of instant fame that tends to be a mixed blessing. “When I made it, I thought I would get the people in the neighborhood to think I was cool, and instead my whole life changed,” she says. “Suddenly I was known around the world as this potty-mouthed, insane, schizophrenic girl.”

But once Phair’s public bought into that girl, they wouldn’t accept a watered-down version. The rift between Phair and her fans began when she revealed that while her songs sounded confessional, they were actually fictionalized. Her two subsequent releases, 1994’s Whip-Smart and 1998’s whitechocolatespaceegg, failed to capture the same attention. Then, in 2003, nearly 10 years to the day after Guyville was released, she put out her self-titled fourth album, a glossy, sterile pop record in stark contrast to the low-fidelity messiness that had characterized her earlier work. To call the response to the album unkind is an understatement. “How are you enjoying life as a sell-out media whore?” began an open letter a fan posted on her blog the day of the new album’s release.

In the five years since then, Phair has kept herself busy, releasing another tepidly received album, recording some songs for soundtrack albums and scoring the new CBS drama Swingtown. But she’s also spent time coming to grips with why her fans felt so outraged by her later work. “Guyville was this thing that spread through word of mouth. They felt like they owned it. And they felt like ‘we elected you to this position, and now you need to deliver.’ They felt betrayed, like I had betrayed that album and them, and I guess I get how that’s a legitimate feeling.”

Guyville, once a point of pride, became a shiny ball-and-chain preventing her from growing artistically. “My fans pulled me away from my work,” she says. “There was a point at which I didn’t feel connected to the songs anymore.” But after 15 years of tug of war with the fans who felt they had to protect the album even from its creator, she’s ready to pull back. To that end, she’ll also be playing a batch of shows in which she’ll perform Guyville in its entirety, including some songs she’s never played live. Relearning the songs is a “nightmare”, but it’s part of the process of coming to peace with her ornery creative offspring. “There’s something lovely and relieving about it,” she says. “It’s like when you have to clean out your closet, and it seems like it’s going to be the most terrible thing in the world, then you do it and go, ‘Oh, that wasn’t so bad’.”