By Bill Wyman

New City Music, March 31, 2016

Every few years, it comes back.

Back in 1994, I had a weekly music column called “Hitsville” in The Chicago Reader. In early January of that year, I put together a top-ten list of albums from 1993 with an accompanying essay. It was all maybe 700 words. Strikingly, two entries by Chicago acts—Liz Phair’s debut, “Exile in Guyville,” and Urge Overkill’s first record for Geffen, “Saturation”—topped my list.

Steve Albini, then as now, was an iconoclastic music producer on the underground rock scene. He was pissed off by the piece; and in full dyspeptic mode he sent a letter to the paper. It was printed under the headline, “Three Pandering Sluts and their Music Press Stooge.”

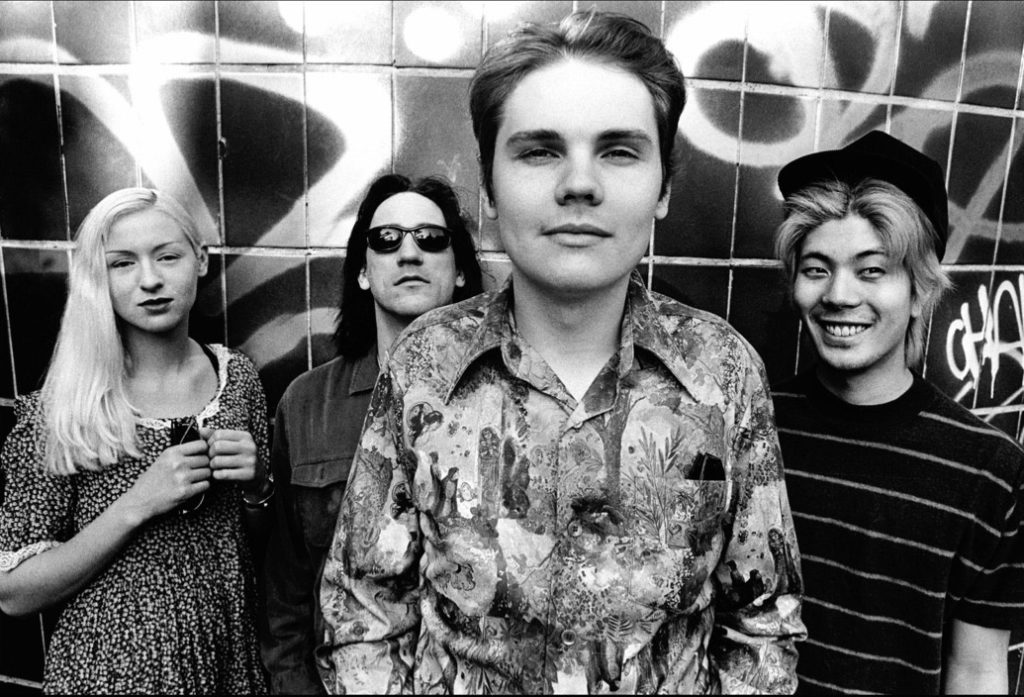

The pandering sluts—his words—were the two acts I just mentioned and another Chicago outfit, the Smashing Pumpkins.

I was the stooge!

The letter was long and vituperative and hilarious: “You only think they are noteworthy now because some paid publicist has told you they are, and you, fulfilling your obligation as part of the publicity engine that drives the music industry, spurt about them on cue.”

Back then, the Reader was a huge institution. The paper came out on Thursday, stacked like bricks in walls three-feet high in stores and cafes. “Hitsville” was on the front page of Section Three. Albini’s little missive set off a letters war of seemingly unending scorn and heat that played out week after week in the paper, with rafts of responses, insults, counter-responses and counter-counter-responses.

In later years, after the Internet took hold, the letter was endlessly cited in adoring profiles of Albini, or histories of the Chicago music scene of the time. Ten years later, Ana Marie Cox wrote a hefty piece about it for the Reader itself, and just a few weeks ago—twenty-two years later!—the Reader’s music editor, Philip Montoro, brought it all up again amid news that the Pumpkins and Phair were going out on the road together. (They’re playing the Civic Opera House April 14.). Albini’s letter, he said, had torn me a new orifice. And he concurred with Albini’s judgment that I was there to promote popular bands: “Like many music writers, Wyman clearly considered the size of his potential audience when deciding which artists to cover.”

On examination, I was grateful to se that I had the requisite number of orifices, but even so, Montoro’s column got me feeling all misty. I started to remember what the scene was like back then.

As Montoro and many others have noted, I never responded to Albini’s billet-doux. Why? Because the Reader’s general policy was that writers shouldn’t respond to letters. The writers had had their say; it wasn’t fair for them to jump in after and claim the last word.

On the other hand, if there was an actual, factual dispute, the writer did have to respond, and clear the matter up one way or the other. Indeed, long after I’d left the paper, an editor called to ask about a letter that had just come in, for some insane reason, challenging something I’d written nearly a decade before. I looked it up. The writer was correct! I duly responded with a correction.

Anyway, the real reason was that we knew that readers were smart enough to make up their own minds. I also trusted that they could see that Albini’s letter for what it was.

But now, with a new generation of writers weighing in, there’s a new audience, too, who can’t know the context of the controversy.

It got me thinking: Maybe it was finally time to tell the true story of what happened in 1993, the greatest goddamn year in Chicago rock history.

If you care, here’s how it all went down.

Our story begins on a cold and snowy Chicago night, almost exactly a year to the day before the publication of the column that got Albini’s spectacles foggy. I was at Lounge Ax, one of the coolest clubs in the city. (In August 1995, co-owner Sue Miller would marry Jeff Tweedy there at a wedding attended by many of the characters in this story.)

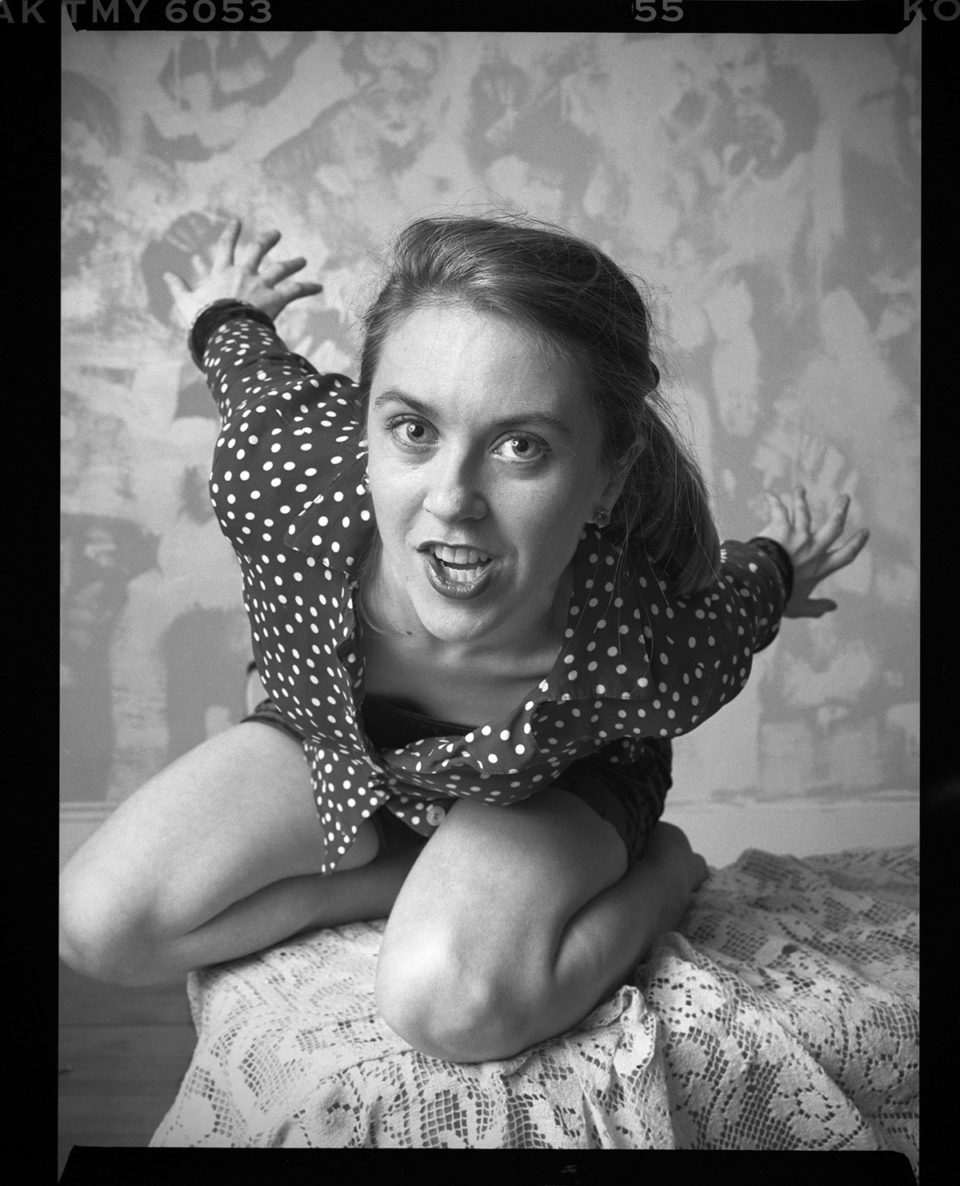

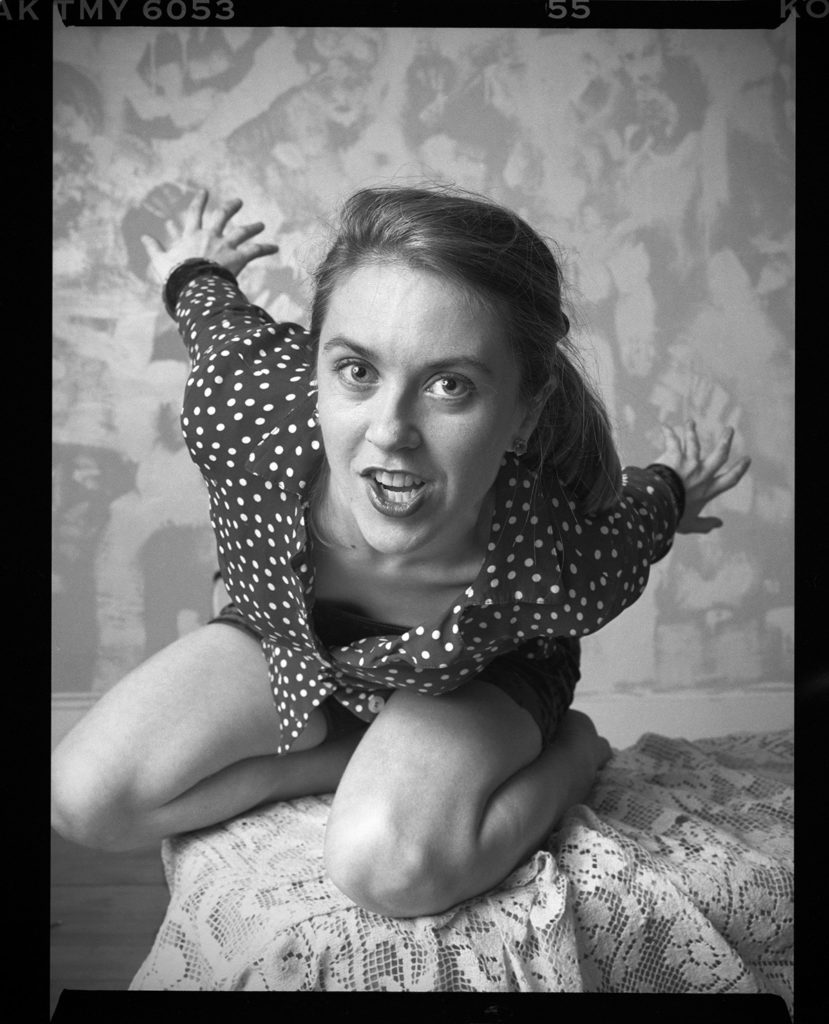

It was late; shows started at midnight or after. Sipping my Coke at the bar—I didn’t drink—I met a tiny singer-songwriter. She was a friend of friends. She gave me an unmarked cassette—a collection of songs she’d been working on—jabbering all the while.

Her talk was something: fast, slightly nutty, kind of winning. There was a lot of TMI, incessant and creative profanity, combative observations on the music scene and more. Some of her opinions about music cracked me up, particularly what she said about her tape. It was, she said, “a song-by-song refutation of ‘Exile on Main Street.’”

“Mm-hmm,” I thought, and put the tape in my coat pocket.

It was a crazy time in music. This was January 1993, remember, the morning after a crazy music year. Nineteen ninety-two was when the full force of Nirvana’s “Nevermind” had basically blown up the music industry.

Before Nirvana, pressure had been building a long time. Back in the 1980s, there were all these cool bands—the Pixies, Sonic Youth, the Replacements, Hüsker Dü, Black Flag, Fugazi—and gazillions more lost to history. Some of the music was tuneful, a subspecies of mainstream rock or even pop; some was harsher, with subject matter to match.

Here’s the thing, though. Whatever the sound, none of this stuff got played on commercial radio. Period. This was the era of a shitty soundscape of Live Aid geezers—Clapton, Petty, Mellencamp, you know the type—amid a new age of neo-hard rock, epitomized by onetime Sunset Strip gutter denizens like Mötley Crüe and Guns N’ Roses.

There was no YouTube or Facebook or Twitter or Spotify to take refuge in. There was word of mouth, a few battered photocopied fanzines, maybe a show or two on a local college station and, once in a while, some airplay on MTV’s weekly “120 Minutes.”

Otherwise you (a) looked for a friend who had a particular record or (b) bought it.

Hard to believe—people actually had to pay for music.

I was a critic, and we were ahead of this game; we got our records for free. It was a nice racket, sure, and it was nice work if you could get it, but it was also a responsibility. A lot of the listening was what Robert Christgau called “processing”: putting on unmarked advance cassettes or pulling a vinyl platter by a band you’d never heard of out of a sleeve and looking for a new sound—or just a great song.

It was your job to find it. Those generic cassettes were a job, but also receptacles of danger and promise. You were alone and confronted with a record that might or might not be something special. Once in a while something hit hard. (One I remember turned out to be PJ Harvey’s first album, “Dry,” which I gave an A+ in Entertainment Weekly.)

Forgive me if I provide a little more background, but some of this will have relevance later on.

One of the Reader organization’s philosophical precepts was that you didn’t write about stuff to “cover” it, and you didn’t make sure things “got covered.” You wrote about things because you had something interesting to say about them. Editors didn’t make assignments. I can’t underscore enough how outlandish this approach to journalism was back then, even in the alternative world. We tried to imagine a “curious and intelligent but disinterested reader”—someone who didn’t have any stake in the discussion, but who might be interested in a reasonably intelligent and coherent take on it and maybe the chops to express it.

When I came on board I was the Reader’s youngest staff writer, and I was proud to be there. I looked for things that captured my imagination or spoke to me in an unexpected way. I wrote pieces about some crappy bands I now think were mistakes, but I remember most the unusual ones that demanded more listening, and eventually made me write about them. The Vulgar Boatmen is a good example—a debut record on an unknown label that came in the mail. I ended up writing about it incessantly. (I just did a twenty-fifth-anniversary piece about the band for The New Yorker’s website.)

Since I worked at the Reader, my gig was much different than a lot of critics’ jobs. Back then there were only two ways for an artist to sell records. You had to get radio airplay, and you had to tour. The touring had a tangential effect: the articles about the band written in the local papers in the towns they traveled through. Over time, it could create national awareness for an act. (Consider: Back then the L.A. Times, say, might have had a circulation of a million, which translated into three or four million potential readers. A story there was a big deal, far more than the 400 people who might come out to see a club act—or even 15,000 who might see a big show at the L.A. Forum.) So most music critics faced a weekly grind of “phoner” interviews for previews of bands coming through town. Key point: These interviews—and hence the coverage—were initiated by the labels. Their press people were on the phones constantly, doling out slots. Artists would spend a few days before the tour got under way—and then during off hours as the tour went on—yakking on the phone in twenty-minute segments, just to get some upbeat advance coverage.

I rarely did those. (I want to say “never” but won’t in case I’m forgetting something.) When I did interview someone, it was because I had heard the record and wanted to talk to the artist. I’d call up the record company and try to set up a talk, but this would almost always be difficult, because it wasn’t part of their PR plan.

I had the quaint notion that they were there to help me out in my work, rather than vice versa. That didn’t make me too popular with label types; but over the years I developed a reputation, partly because I did a lot of “critic’s choices” for shows and other more substantive pieces, and partly from being on panels at SXSW and elsewhere. (One of them, held in the biggest convention room in Austin, was entitled “Were The Grateful Dead Really Any Good?” and nearly provoked a riot.) Record labels were a big deal back then, and I have to say that most of the folks who worked for them were, in the end, professional. Sometimes I’d get yelled at (a lot of my Critic’s Choices were perversely negative), but I wasn’t shunned. Mostly I was tolerated as an amiable if slightly challenged child.

The other regular duty of the typical local critic at the time was to crank out friendly profiles about popular or promising bands on the local scene. I didn’t do those, either. A test I had: I was looking for a track on a demo tape that I might play for a friend and say, “Listen—this is a great song!” There weren’t too many of those. (It still makes me sad to hear “Renee Remains the Same.”) I didn’t think groups should get brownie points for being local. Music was music, and I held local acts to the same standard I did national ones.

One last thing, to finish setting the scene: Jim DeRogatis had moved to town to be the pop music critic at the Sun-Times. The first few times we met he wouldn’t talk to me. After the third time he blew me off at the Metro my girlfriend had had enough: “What is up his butt?” she asked.

It transpired that Jim had been offended by a SXSW panel I’d done on the writer Lester Bangs, his hero. (I hadn’t been sufficiently adulatory.) Jim was and is a tremendous person, one with a bedrock and fearless humanity marred only by a critical apparatus that is virtually always wrong.

A prime example of this was that he thought the exact same thing about mine.

We eventually took our arguing onto the radio, and started “Sound Opinions,” a Siskel-and-Ebert-style music talk show, on The Loop, then one of the biggest rock stations in the country.

As I said, the industry was just dealing with the big “Nevermind” hangover. The Loop, for example, was finding the idea of FM rock radio shift beneath its feet. Here’s an example of how different the time was: The show Jim and I did after Kurt Cobain’s suicide—a memorable program in which we opened the phones to listeners to talk about his music—was greeted with eye-rolls at the station. But in the end, to the station’s credit, there and later on Q101, we talked about, and played, all sorts of genres you wouldn’t expect, from country to hip hop to doo-wop. Now of course the show is a powerhouse public radio staple with Jim and the Trib’s Greg Kot.

All of this is to say that I basically wrote about, and talked about, stuff I thought I had something intelligent to say about, and that readers might find interesting. I’m not saying any or all of it actually was intelligent, just that that’s what guided my approach to writing.

With a few exceptions, generally involving record deals and such—Eleventh Dream Day, Material Issue, and R. Kelly come to mind—I hadn’t written much about local groups.

And in my weekly “Hitsville” column, unless I’m forgetting someone, I don’t think I ever did just a straight-up profile of the “Here’s this person on the local scene who recorded a good album” variety…