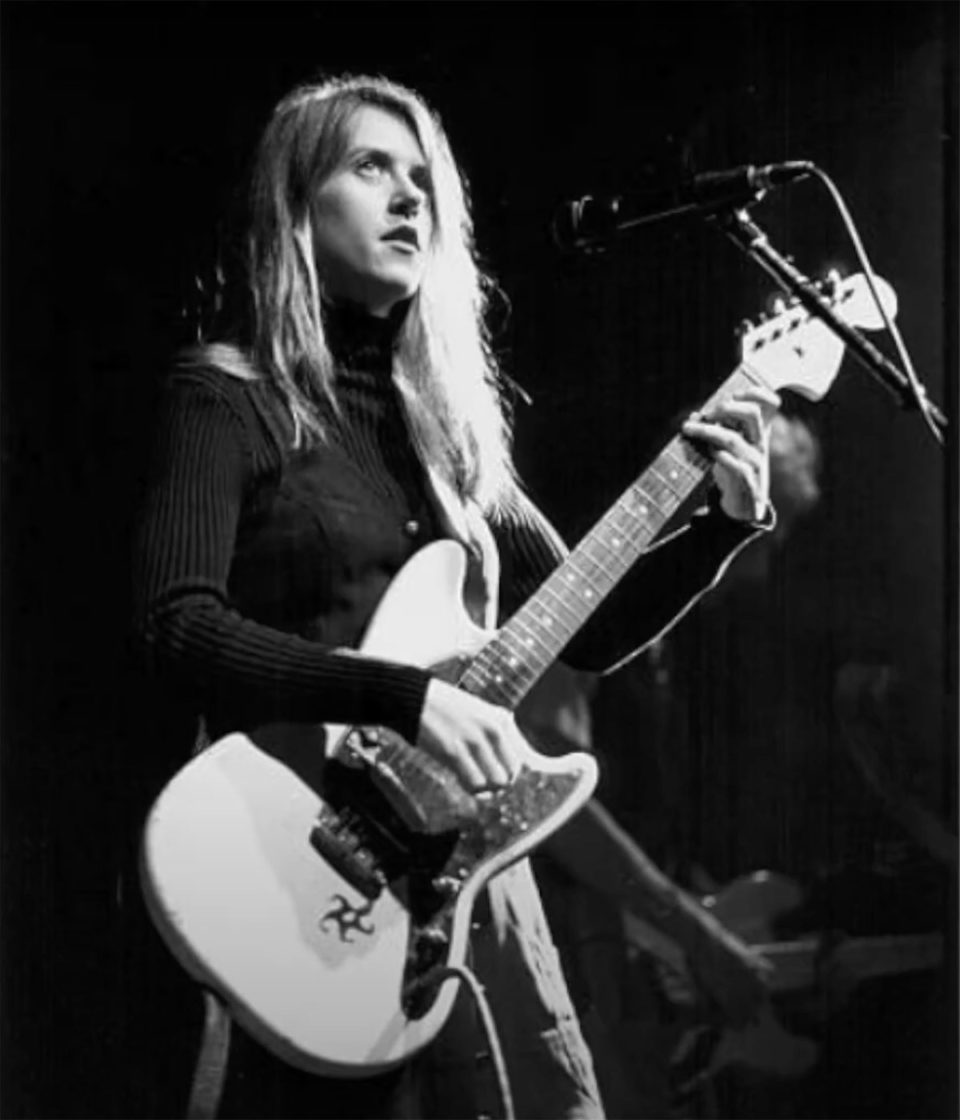

I forgot about the cassette the woman at the bar had given me until the next day. The first song (“6’1″”) was pretty good, but all bands put their best song first on their tapes. The second song was more difficult, but I noticed the phrase “weave my disgust into fame.” The fourth song was delivered in an unsteady but riveting soprano, and the fifth (“Never Said”) was better than the first one. I started to realize that everything, from the lyrics to the musical styles to her voice, was not only different on every song, but different in a lulling and sometimes thrilling way. That’s when the babbling at Lounge Ax began to make sense. I called Phair and we had breakfast at the original Wishbone on Grand the next morning, still snowy.

I was the first person ever to interview her, and it was a lot of fun. By that time the album was basically done and Matador was making plans to release it. She wasn’t known as a local club act, and getting signed this way was an end run around the local scene, which I think in retrospect laid the foundation for some of the skepticism and disdain for her that evinced itself later.

My talk with her was the next week’s “Hitsville” column, which came out that Thursday. I wanted to call it “Straight Outta Guyville.” (N.W.A. reference.) The Reader went with “Greetings from Guyville.” (Bruce Springsteen reference.) Here’s what I wrote:

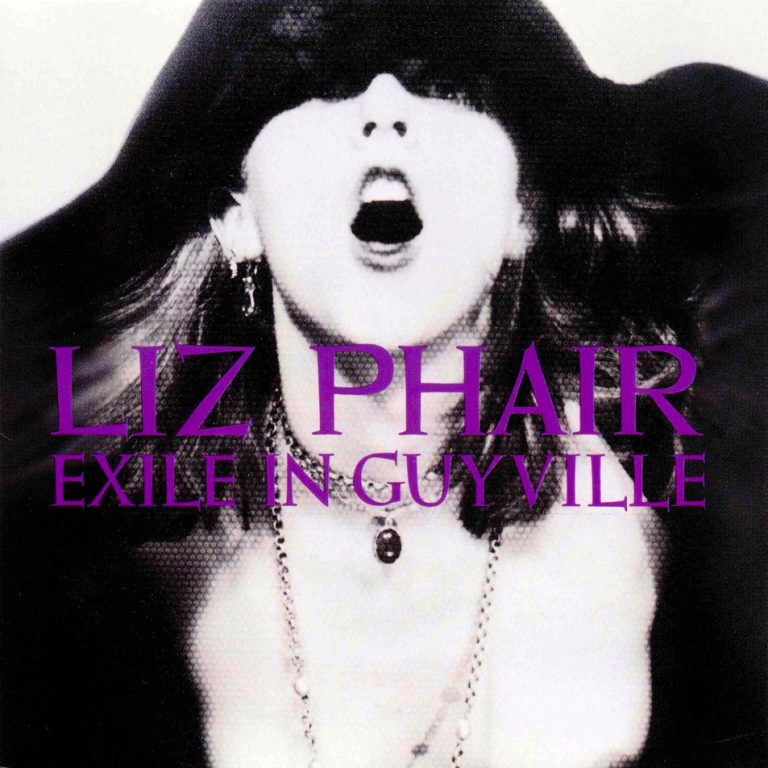

While no one knows what Exile on Main St. is really about, I’d venture to say that it has something to do with the addictive, debilitating toxicity of things like sex, love, and rock ‘n’ roll. Those are Phair’s subjects as well, but while she acknowledges the dark side of the equation, she runs it all through a giddy, girl-o-centric grinder. Exile in Guyville’s epic contextualization is leavened by an unshakable pop-rock sensibility (“You can say I like classic rock”) that ties irresistible melodies and friendly, sometimes anthemic guitar riffs to recurring themes of lovesickness, carnality, emotional laceration, and the inter- and intramural gender wars. Her theses are sweeping and cheerfully kaleidoscopic, from postfeminist mournfulness (“Whatever happened to a boyfriend / The kind of guy who makes love ’cause he’s in it?”) to post-postfeminist horniness (“I want to be your blowjob queen”), from dissections of the male psyche (“I bet you fall in bed too easily”) to her own (“I get away / Almost every day / With what the girls call murder”)…

It’s a bit lo-fi, but utterly convincing as it wildly dispenses bits of Big Star pop deliciousness (“Never Said”), effortless tune making (“Help Me, Mary”), irreproachable alternative rock (“6’1″, “Fuck and Run”), Joni Mitchell-y balladry (“Dance of the Seven Veils,” though Joni Mitchell never used the word “cunt” in a song), occasional nods to guitar dissonance à la Pavement or Sonic Youth (“Johnny Sunshine”), and even Fleetwood Mac-ish atmospherics (“Explain It to Me”).

Every time I listened to the album over the next year I found new things to be impressed by. More than once I talked to colleagues in other cities—one I remember was Tim White at Billboard—and together we’d enthusiastically unpack some of the record’s secrets, from Phair’s songs to the massive sonic coup that was Brad Wood’s production.

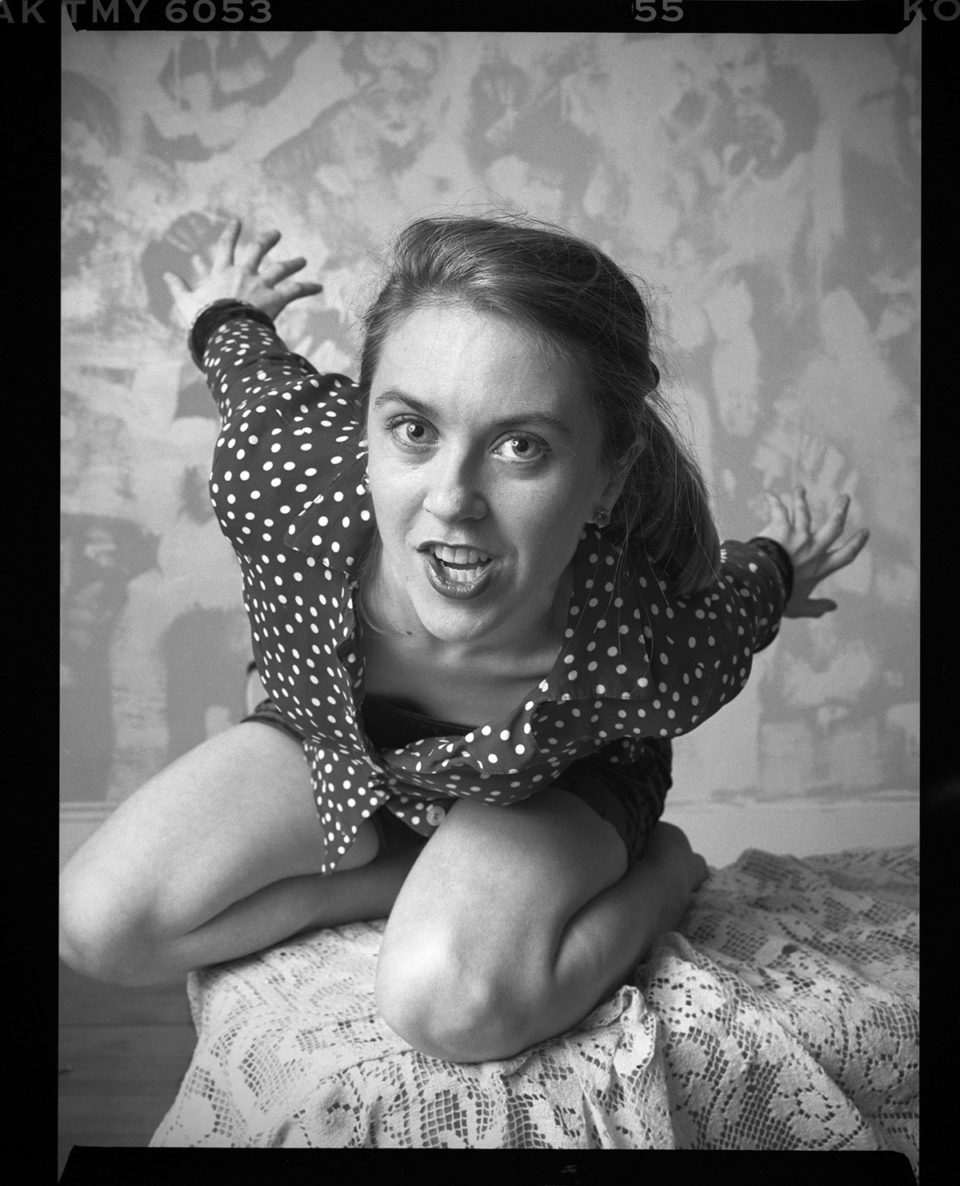

The next six months or so, as expectations grew for the release of the album, were delightful. I had the tape and could lord my possession of it over everyone else. I tracked Phair’s every local appearance and delighted in the exasperation I sometimes heard. Phair and I kept talking, always as reporter and subject, and all of the conversations were taped. I knew the record would be a critic’s darling, but in Phair herself you could see the makings of an actual star. She was disturbingly, instinctively talented and poised; extremely good-looking and seemingly intent on sexualizing her persona; and sparklingly intelligent.

Somewhere I still have the napkin on which she sketched out her plans for the cover. This was the now iconic “blowjob queen” photobooth shot, done under the direction of Urge Overkill’s National Kato, with careful attention paid to the just-right cropping of her left nipple—accompanied by a rapid exposition of the signifiers of each piece of the shot: that nipple, the hood, the hair, the open mouth, the lipstick and so on.

Phair could take care of herself, of course. She’d opened up the debate, after all, with the title of the album. “Guyville” was a reference to the Urge Overkill song “Goodbye to Guyville,” and in Phair’s hands it became the title of the boy-dominated local rock scene. That said, very early on the background noise on her became elevated. She was fairly privileged, having grown up in Winnetka with a prominent doctor father. So you could say, as many did, that she was a rich kid. But she was adopted too, about which you could say, though few did, that her life could have ended up much differently. Her having signed to Matador, a cool label at the time but a blip on the cultural landscape, was seen as selling out. Her halting first performances were laughed at. And her personal life was talked about endlessly.

I like gossip; the free flow of information is great for journalists, particularly back then, when I was one of the few people who had a public outlet for it. But I gotta say a lot of it was heavily sexualized and felt hostile. One letter-to-the-editor slamming Phair said I was trying to get “a whiff of Winnetka pussy”; that was typical of the tone. The Chicago Headline Club at its annual comedy show at the Park West did a weird skit that implied we were sleeping together. (This was a little uncalled for; it wasn’t like we were sashaying around town together.) Tension built. Meanwhile, Newcity’s Ben Kim trashed Phair’s live shows; Phair petulantly canceled an interview with Ray Pride, who was working on a proper cover story.

But I still knew what I’d known that Saturday morning: that it was the album of the year, and was, and still is, one of the best records I’ve ever heard. Phair’s trenchant delivery, unflinching flaying of her own peccadilloes, and deceptively high musicality combined for a lethal dose of female power rock.

As the year went on and excitement built, her life got better, though she still didn’t have much money and still was just a person living in a not-particularly swellegant corner of pre-gentrification Wicker Park. Increasingly people recognized her on the street, in stores or in restaurants. Her phone—we all had landlines back then—rang incessantly. (Literally incessantly.)

A lot of the people she talked to seemed to consider her a star already, with some odd ability to do some career-defining, society-changing thing. I remember her saying that a lot of people were telling her, “You know what you should do? You should…” and then being a bit put out when she demurred.

Phair dominated the year, but other things were going on as well. The most flamboyant involved Urge Overkill. Urge was a joke band—they dressed in matching suits, spoke in a hip, neo-Rat Pack patois, adopted the stage names of National Kato, King Roeser and Blackie Onassis—but the joke was that they really weren’t a joke.

Under the tutelage of producer Steve Albini, first on his own ultra-indie label and then Touch and Go, they had recorded a few albums of very rough underground rock, filled with dread and menace. But each release had something new—dynamics, maybe, in “The Supersonic Storybook”; emotion and singing, perhaps, in “Stull.” I saw them a lot and once in a while—I’m thinking of a night at Czar Bar—they were simply awesome. “Storybook” had ended up on my top-ten list a couple of years earlier. (Again, this was a list of national albums, not one of just Chicago acts.) “Urge Overkill are believers in the aesthetic of ugly,” I had written. “The band members are ugly, their name is ugly, their albums are ugly, and their music and lyrics are ugly as well.” This was long before they were the idiot princelings of the scene. They were heavy and smart, and also had songs. You could feel their evolution.

But they’d become estranged from their onetime pal Albini and onetime benefactor Corey Rusk at the label, and were now in the midst of a range war with them. I was happy to be in the middle, collecting quotes like this one from Albini: “I have to admit that my hatred of them is slightly irrational, in that special way that you feel hatred when people who were once good friends turn into pieces of shit.” Among other Algonquin-like mots, Albini called Urge’s “Stull,” “Stool.” Urge called Albini’s “Budd,” “Pud.”

Urge had been signed to Geffen, and were running around opening for Pearl Jam and Nirvana, who liked them a lot. They were going to be on the cover of Spin, then they weren’t, then they were. They were under a lot of pressure. For their new album, they’d worked with a pair of Philadelphia producers who called themselves the Butcher Brothers. The pair had delivered an implacable foundation for the band to expand its attack on top of. “Sister Havana” had one of the great killer choruses of the era; “Back on Me” captured persuasively the band’s talent for making traditional pop sentiments sound vaguely threatening; and “Positive Bleeding,” the band’s best song, was little more than a set of signifiers (that word again) setting hippie and new age positivity against being positive in the age of AIDS—and the video was smart enough to match. The group summed up its smirky politesse in a legend displayed at the start of the clip: May We Rock You?

I was a huge fan, and hanging out listening to their shtick in their Humboldt Park HQ—it was called “the Bank”—was highly entertaining, but I was always viewed with a bit of suspicion, maybe because of the “ugly” riff from a few years before. Some of the coverage of the Albini wars pissed the group off, I think because it embarrassed them when they were trying to keep their press coverage consistent as the album was being released.

Then I did a piece on the Stalkers, a delightful pair of local women who had taken to dressing up as members of Urge and wandering through Rainbo and other clubs mocking them.

“My new record is like the White Album,” the fake Kato would say. “We’re white, and it’s an album.”

There was a slight edge to the scene at the time, much of it brought on by heavy drinking, and here and there drugs. Once in a while, you’d hear about a fight in a bar. One voluble, somewhat overheated scenester, who knew a lot of the people I’m writing about in one way or another, wrote me an agitated, three-page, single-spaced polemic along the lines of Albini’s letter to the editor, except this one had vague references to cracking me with a pool cue at the Empty Bottle—and dropped the news that he owned a gun.

One night at Metro, the band Red Red Meat was playing one of those very late Metro shows. Material Issue’s Jim Ellison, a friend of Kato’s, ran up to the front of the stage with a guy from the band My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult. They doused the band onstage with cups of beer and ran off.

Red Red Meat came to a slow stop, their noses twitching.

“It’s urine all right,” someone eventually said.

So when, around this time, I kept hearing that the Urge boys, Kato in particular, were saying they were going to kick my ass, I took it under advisement. In the early morning hours at Wrigleyville Tap, I sat discussing it with a couple of friends. “Nate’s a pussy,” someone said. “He’s not a threat.” My friend Pat Daly, who published the ‘zine Empire Monthly, looking me up and down, disagreed. “No, we want to keep Billy safe.”

Courtney Love called me late one night. I was one of her (many) AOL IM buddies. (“I love the internet,” Love said. “It’s like a video game about me.“) She was in town. Did I want to come out for a drink at such-and-such a bar? “It’s in Humboldt Park,” she said brightly.

Love went way back with Urge, and Humboldt Park was Urge territory. She didn’t mention the band, and for all I know the call was innocent. (Later on, she denied it wasn’t.) But I wasn’t going to take a chance on winding up the inhabitant of a makeshift torture room in the Bank at the hands of a drunk and pissed-off National Kato. And if she weren’t calling on behalf of Urge, the next question was, what in the hell was she doing in Humboldt Park at 2am? I didn’t see a way this experience would work out well for me.

Nah, I said.

And finally there were the Smashing Pumpkins. Industry word had been growing on them for years. Billy Corgan, talented and pugnacious, was always sort of a head case. Joe Shanahan, who ran Metro, believed in him—and boy, every time you saw them, they got better and better. But I really didn’t get the band. They were one of the groups I simply had nothing to say about. Corgan was interesting—he had a big birthmark running up one arm, which must have been a challenge to deal with as a kid—and grew up with issues. He was fiercely anti-macho but at the same time brooked no one when it came to shaping the band. “I’m not going to apologize for wanting to be great,” he said to me once.

For the first single off “Siamese Dream” he chose “Cherub Rock,” a snarl at the indie scene that hadn’t given him the time of day.

So I always thought Corgan was a smart and classy guy, even though his music didn’t speak to me. He knew I wasn’t into the band but he was never anything but professional and forthcoming when I talked to him. My sense was that he tacitly understood what the Reader did. He co-hosted “Sound Opinions” with me a couple of times when Jimmy was out of town, which he didn’t have to do, and when “Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness”came out—a big deal at the time, after “Siamese Dream” went multiplatinum, with a ballyhooed worldwide radio broadcast of a live show from the Riviera with Cheap Trick—he asked me to do the accompanying interview with the band beforehand. He certainly could have used any MTV VJ or any other star he wanted. I thought it was an example of how he would stick with Chicago people even if they weren’t sycophantic.